How Do We Use Sequels with Our Scenes?

In various posts here, we’ve explored how many concepts in writing don’t quite match the general understanding of a word or phrase. That’s why I start many posts with basic definitions to ensure we’re all on the same page.

But of the many words with confusing meanings in the writing world, probably none are more confusing than scenes and sequels, both words that refer to multiple concepts in the writing world. Once we’re all clear on some common definitions, today let’s look at the purpose of sequels in our story and how to write them. *smile*

Definitions: Types of Scenes and Sequels

Starting with the basics of scenes, there are 3 ways we tend to use the word:

- Setting-Focused Scene: The school-style definition is an event in a specific place and/or time. When the setting changes, it’s a new scene. (Note: This definition is almost never relevant to writers, as the other definitions make more sense for how we write.)

- Storytelling Scene: A mini-arc of events that usually occur in a specific point of view (POV) (and sometimes a specific time/place). When the arc reaches a satisfying ending, such as a hook or emphasis of a point, a line break or chapter break marks the end of the scene.

- Goal-Focused Scene: This is the first half of the idea of scenes and sequels, from Dwight Swain’s book, Techniques of the Selling Writer. This definition of scene focuses on goals and actions.

In addition, we tend to use the word sequels in 2 different ways:

- Book Sequel: If we write our books in a series, we’re familiar with a book sequel, which might include similar characters, settings, worldbuilding, etc.

- Reaction-Focused Sequel: This is the second half of Dwight Swain’s idea of scenes and sequels. This definition of sequel focuses on character reactions.

In today’s post, we’re digging into the last definition for each of those words, and we’ll capitalize them to make these meanings clear: goal-focused Scenes and reaction-focused Sequels.

Actions and Reactions

Before we get more into those last definitions of Scenes and Sequels, let’s first get even more granular and talk about actions and reactions. Readers are carried through our story by its flow, its cause-and-effect chain.

What is a scene's sequel and how do we use them? Click To TweetWe find a chain of actions (stimulus/motivation/cause) and reactions (response/effect) everywhere from the large scale of a story’s acts and beats to the small scale of sentences and paragraphs, what Dwight Swain calls Motivation-Reaction Units (MRUs). No matter the scale of our perspective, the response to the previous action becomes the stimulus to the next response, and so on until the end of the story.

Scenes and Sequels are a big part of this cause-and-effect chain as well. A Scene’s actions are the stimulus to a Sequel’s reactions. The Sequel then ends with a decision about the character’s goal, kicking off the next Scene…and so on.

Scenes vs. Sequels

Some people really hate the idea of Scenes and Sequels, either thinking them too confusing or too outdated to apply to how we write. But the truth is that Scenes and Sequels are important for ensuring we’ve created a satisfying story for readers.

So what are Scenes and Sequels? They’re simply a passage of writing that either shows a character trying to make progress toward a goal (Scenes) or shows a character reacting to the situation’s outcome (Sequels).

Scenes are made up of:

- Goal: What the protagonist wants at the beginning of the scene.

- Conflict: The obstacles standing in the way.

- Disaster: The outcome, what happens that prevents the protagonist from reaching their goal.

Think: Scenes consist of Goals and Setbacks as characters take action to move the story forward.

Sequels are made up of:

- Reaction: How the character reacts to the Disaster.

- Dilemma: The choice the character faces because of the Disaster.

- Decision: What the character decides to do next (new goal or new attempt to reach old goal).

Think: Sequels consist of Reacting and Analyzing as characters absorb and apply the lessons learned.

In other words, Scenes tend to be more plot or action-oriented (proactive), and Sequels tend to be more character or reaction-oriented (reactive).

Are Sequels “Bad” for Our Story?

Given those explanations, we might wonder if Sequels are “bad” for our story. After all, we’re often advised to ensure our character is proactive rather than reactive.

If the sequel to a scene is all about reaction, does that mean it's bad for our story? Click To TweetIn fact, in the comments of an old post here, Ben recently asked how to interpret the latest advice he’d seen about de-emphasizing the use of Sequels. If we think of Sequels only as being a page or more of “navel gazing,” a de-emphasis makes sense, as we wouldn’t want to slow down our story that much.

But Sequels are far more flexible than that idea. Instead of thinking of a scene-length reaction, think of Sequels as being how our story and our protagonist answers the question: Now what?

Sequels Are Necessary for Our Story

From our readers’ perspective, our stories are about far more than just “the things that happen.” Our stories are about emotions. If we don’t evoke any emotions in our readers, we’ve failed to tell a compelling story.

What's the purpose of a scene's sequel? Why does our story need them? Click To TweetThe goals and actions and situations we create in all our Scenes can indirectly lead to emotional understanding for readers. If readers know the protagonist’s goal is important and sees them fall short, they’ll feel some sort of emotion, right?

But wait… How would readers know the goal is important?

Beyond an obvious sort of goal like “save the world,” how would readers understand and relate to our protagonist’s motivation for pursuing the goal? How would readers really know how that failure affects our character?

Answer: Sequels. A Scene’s Sequel lets us dig more into our characters and emotions. In other words, Sequels are where we tie the plot events to our character’s internal/emotional arc.

The Purpose of Sequels

We know from our real life that when we experience a setback, we need to process it and decide how to move forward. That need to recover is basic psychology.

Yes, many times readers can infer how our characters feel after a setback, but we often want to take the chance to show our character’s reaction too. If our characters skip that step completely because we don’t show any reaction from them, our stories and characters won’t ring true. We’ll also miss out on many opportunities to create emotional resonances with our readers—to make them care.

So to better understand how we should use Sequels, let’s first review all the ways they serve a purpose for our storytelling.

Sequels allow for…

- Reaction: our character reacts to and processes setbacks, showing their emotions and thoughts in regards to their circumstances

Characters experience internal feelings and reflexes of their immediate emotional response, helping readers relate to the character: They might stagger off-kilter, feel physical pain, be disappointed or angry, etc. - Dilemma: our character analyzes how to move forward despite setbacks

Characters experience internal thoughts or dialogue of rational reactions and anticipate likely outcomes of options, giving readers insights into the character’s internal goals and/or motivations: They wonder how to get out of their predicament, try to identify any “lessons learned,” and think through their options. - Decision: our character figures out their least bad option for how to move forward

Characters experience internal thoughts or dialogue of plans and goals, letting readers know what to root for next: They decide what goal to work toward now or to make another attempt at the previous goal, kicking off the next Scene.

In addition, Sequels also serve a purpose with our story’s…

Pacing:

The ratio of word length for our Scenes (action) to Sequels (reaction) helps us control the pacing of our story. In fact, this ratio is one of the biggest factors affecting our story’s pacing. The longer our Sequels, the slower our story’s pace. The shorter (most of) our Sequels are, the faster our story’s pace, as the action will be predominant.

Backstory:

Sequels are where most of our characters’ backstory is revealed, either with subtext of their concerns, decisions, and motivations, or outright with flashbacks. Almost by definition, flashbacks need to happen in Sequels, as flashbacks occur when characters are feeling reflective about how their past applies to the present.

Stakes:

Sequels show (or at least hint at the beginnings of) the consequences of failing to reach goals. So Sequels strengthen our story’s stakes, which helps with pacing and tension.

Character Arc:

Our character changes as they face situations and make decisions about how to react and/or overcome. Those decisions and reactions are all a part of Sequels. Sequels are also where we find the internal monologue and thoughts of epiphanies, as they learn lessons from events of various Scenes.

Theme:

Our story’s themes are often developed by what our characters learn and/or the choices they make. Both of those aspects live in Sequels. To create a strong theme, we need to show our character facing decisions, making priorities, reflecting on their losses, etc. The subtext behind those decisions and reflections reveals the theme.

Meaning:

Sequels help us add meaning to our story. The story pieces we spend time on reveal what aspects of our story are important. Our characters react and debate and decide because these events and setbacks matter to them. If events don’t affect them, the events don’t matter.

Cause/Effect:

As we discussed above, the cause-and-effect chain applies at every level of storytelling. At this level, the Scene is the cause, and the Sequel is the effect, which then acts as the stimulus for the next Scene because of the Decision setting a goal. Without a Sequel, the cause-and-effect chain is broken, stalling our story.

Major Story Beats:

While plot events often force the major choices our characters need to make, the actual turning points of most of our story’s major beats take place in Sequels:

- The first plot point around the 25% mark often involves our character making a major decision to step away from their “normal” world.

- The Midpoint, where the character has a clearer idea of what stands in the way of the story goal, often involves significant reflection, as they weigh how much pursuing their story goal will affect them.

- The Black Moment often explores the stakes/consequences of failure and digs into the emotional fallout affecting the character.

- While the plot Climax might not include significant Sequels (in order to speed up the pace), the character’s internal/emotional arc Climax often includes an epiphany for our character, as they realize a “lesson learned.”

How Do We Use Sequels in Our Writing?

As I mentioned in Ben’s and my conversation in the comments of that post, I suspect many writers think of Sequels as being scene length on their own. With that misunderstanding, it’s no wonder that some might advise writers to skip Sequels, but that’s not how we actually write or use them.

Honestly, we can ignore most of the “rules” about sequels. Sequels are far more flexible than many think.

Just from the point of view of Sequel length, sure, we might include a separate storytelling-style scene of a long Sequel to fully explore the fallout of a major failure, such as after the Black Moment. Or if there’s been a delay between the Scene and the Sequel, such as a different POV character’s scene in between them, we might want a longer sequel, just to include a bit of a recap to remind readers where the character had left off.

However, Sequels will often fall at the end of our storytelling-style scene, with just a few sentences or paragraphs, or the steps of a Sequel might be smashed together or just implied. In fact, a storytelling-style scene—the ones between our line or chapter breaks—might include several Scenes and Sequels, as a storytelling scene has its own emotional arc like a mini-story that can include multiple setbacks and regroupings to try again.

Either way, the point of Sequels is to make our Scenes, and thus our story, stronger. They emphasize what matters in our story.

Other Ways to Be Flexible with Sequels

There’s really no way to teach how to write Sequels “right” because they are so flexible. Those who think Sequels should be avoided don’t really understand them or their purpose. For just a few more examples of their flexibility…

Two Scenes might occur in a row because the usual Sequel is interrupted with a new Scene. Think of stories where a character is musing (or is ready to muse) about how to handle a situation and then a surprise forces characters to navigate a new Disaster or to change their goals overall.

Some Sequels are all internal monologue, as they react and internally debate options. Other Sequels look like a Scene because it’s a conversation with another character, as they toss opinions about their choices back and forth.

Or looking even more like a Scene… That angry fight scene in our story, where the character isn’t thinking, just reacting to a setback? Whether the fight is with words or weapons, it might be a Sequel despite the “action.” What matters is what happens with the character’s internal reaction and setting up the next Scene.

In other words, there’s not one “right” way to include Sequels in our story. Each Scene might take a different approach, depending on its context and importance, along with our pacing needs.

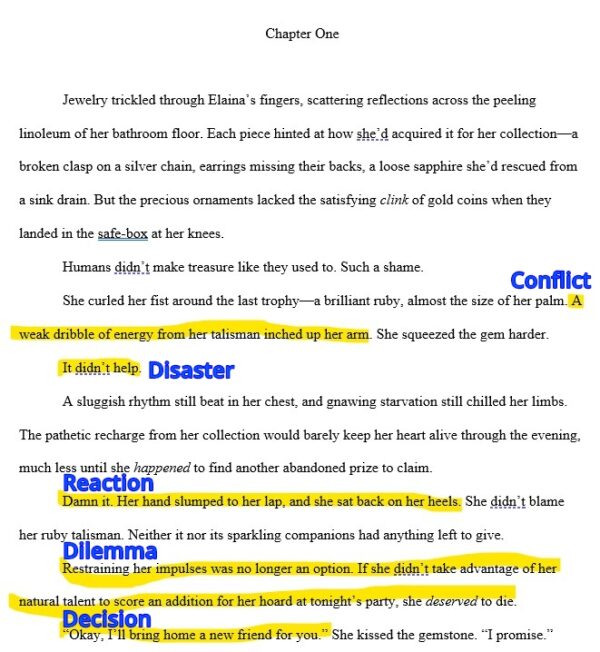

Example: First Page of Treasured Claim

It can be hard to understand what actually creates Scenes and Sequels, so let me give an example from the first page of my novel Treasured Claim. I picked this example because it shows a whole Scene and Sequel, all on one page.

After this point, the Scenes get longer, but at the beginning of a story, getting to a Sequel’s Decision to establish a goal right away can also work well. The point is that Sequels don’t need to be nearly as complex as writers might assume.

Note that I didn’t mark a Goal for the Scene aspect of this example because it’s only implied by the subtext. That’s another reason why setting up a quick Scene/Sequel pair at the beginning of our story might help propel our story forward with a stronger, more explicit goal.

Also note that another Scene starts right after this line, as she starts taking action on that new goal. There’s no line break after this for a separation of a storytelling-style scene. As I mentioned above, a storytelling-style scene can include multiple Scenes and Sequels because the former is about the mini-story arc.

The line breaks of storytelling-style scenes don’t need to be related to these Scene and Sequel pairs at all. We could break after a Scene’s Disaster for a bit of cliffhanger feel, or we could break after a Sequel’s Reaction to emphasize the emotional impact, or we could break after a Sequel’s Dilemma to enhance the “now what?” dread, etc. Whatever our choice, we’d just pick up in the next storytelling-style scene with that character (or characters) wherever we left off.

What’s the Right Length for Our Sequel?

Since so much of the bad reputation of Sequels focuses on the assumption of them always being long, let’s talk more about our choices for length. Getting the right length of our Sequels for the right pacing is a balancing act.

The length of each section can vary from Sequel to Sequel or from one genre to another as well. Romance emphasizes emotional responses in the Reaction section, while horror might focus on the dread of the choices awaiting the characters in the Dilemma portion.

The “right” length and structure of a Sequel depends on the context of the story before that point and our pacing preferences:

Reaction:

How big of a response is appropriate for the size of the setback Disaster? How long of a response is appropriate for the pacing we want?

- If the Scene featured our POV character for the Sequel, they might have been reacting all along, so a separate Sequel-Reaction isn’t as necessary or it could be short.

- On the other hand, if the Scene was from character A’s POV but the events would greatly affect character B, after a line break we might start off character B’s POV storytelling-style scene with a longer Sequel to catch up on their reactions to those previous events.

- Or if we want to get across major devastation, we might need paragraphs, or even pages, of emotion to convey the level of the upset and evoke the emotions we want.

Dilemma:

How fast does the character need to make their choice? Would their choice be obvious?

- With a split-second decision or when the decision would be obvious, we can skip the Dilemma part of the Sequel just to avoid a sense of redundancy.

- If that’s not the case, we can spend sentences, paragraphs, or pages debating the pros and cons of various options depending on the importance and pacing we want to convey.

- Or if we want to emphasize their rock-and-a-hard-place situation, we might dwell on how there are no good options to increase tension.

Decision:

Are they deciding on a new goal or just trying again for the previous goal?

- New goals need more explanation to help transition to and kick off the next Scene, as without a strong sense of the new goal, the cause-and-effect chain would weaken.

- But we don’t need to restate the goal reached out of a Decision if obvious or repetitive, such as if it’s just a continuation or there isn’t much of a choice other than giving up.

- Other decisions mark a turning point for our character and their arc, such as from the result of an epiphany, and those should get more emphasis.

Do Our Scenes Need Sequels?

So to get back to Ben’s question, yes, our story needs Sequels. If we ever completely skip a Sequel—our character’s reactions to events—we should have a reason because how our characters react to events shapes how readers react to our story.

In other words, Scenes are often our plot, and Sequels are often our story. That’s where the “heart” of our story lies, where we set up emotions, themes, meanings, reader anticipation, internal character elements, the personal/impersonal level of the POV, etc.

That said, occasionally some Sequels might be so short and/or implied that they barely exist, and some might assume they’re not there at all. Or surprising events might interrupt our characters’ reactions, creating two Scenes in a row. If the story flow works, it works.

It’s up to us, our genre, our writing style, and our story to determine the “right” approach for our Sequels. Some of our Sequels might be a three page long internal debate, and others might be as simple as: Crap! That didn’t work. Time for Plan B. *smile*

Have you heard of scene Sequels before? Did you know how to use them? Or did you think it was better to avoid them for faster pacing? Do you understand how flexible they can be? Or why they’re important for our story? Do you have any insights into Sequels to share?

Pin It

Hi Jami – I’ve been pondering a question about scene/sequel, and found your blog. My question: In the scene/sequel concept, what are the sex scenes? It feels like they don’t fall into either. I could argue sex scenes are, well, scenes because at least one or both parties have a goal–to get in bed together, but they fail the definition, because they lack real conflict. But they are also emotion filled, as we often see the action results in feelings throughout the same scene.

What’s your approach when analyzing scene/sequel–how do you categorize the romantic action?

Hi Jenna,

That’s a great question about scenes and sequels. In fact, your comment inspired me to write a whole post. LOL!

Check out my answer with more information about how to recognize whether a passage we’ve written is either a scene or a sequel here. Sorry for the delayed response, but thanks for the idea!

Thank you, Jami! This is one of the clearest explanations of sequels I have ever read. Very helpful!

Nope, sorry, I’m dyslexic and my brain failed utterly to process this.

Hi Lindsey,

Oh no! This topic is complicated under the best of circumstances, much less with dyslexia. Let me know if there’s anything I can do to help!

Hi Jami,

Thanks for the offer but I’ve found from past experience I have to work it out for myself 🙂

On a re-read I’ve come to conclusion it was the unconventional use of ‘sequel’ that was creating a minefield. By substituting ‘ramification’ it has finally made sense 🙂

Hi Lindsey,

Yes, “ramification” works well for getting at the meaning! 🙂

The only reason I used the term “sequel” is because that’s how Dwight Swain — who came up with the concept — worded it. I’ve never liked that term either, because it is so confusing. *sigh* But the important thing is to understand the concept, and it sounds like you’ve got it. 😀

[…] more about how to use sequels with our scenes, check out this post on my blog. Do you have any questions or insights about Dwight Swain’s concept of sequels and how the right […]