Does Conflict Really Belong on Every Page? — Guest: Angela Ackerman

As I mentioned a few months ago on Angela Ackerman’s last guest post here:

“A common piece of advice is to include some type of conflict on every page. For new writers, that advice might bring to mind scenes of characters fighting, but the truth of what counts as conflict is much broader than that.”

I’ve often pointed out that when we become writers, we have to “relearn” what some common terms mean in the context of writing and storytelling. Conflict is one of those terms that has a difference context within our writing world than we might expect, one much closer to including anything that creates obstacles or tension in the story.

So let’s dig into this broad view of conflict. Where all can we find conflict in our story? What types of conflict are there? And finally, how can we make every aspect of conflict in our story as powerful as possible?

The fantastic Angela Ackerman—one half of the duo behind the popular writing Thesaurus collection, the Writers Helping Writers site, and the One Stop for Writers resource—is here to help us understand what conflict really means. Once we better understand, we’ll know how we can draw from all the different layers of conflict to include it on every page of our story.

Please welcome Angela Ackerman! *smile*

*****

The Four Levels of Story Conflict

By Angela Ackerman

A cardinal sin of storytelling is to skimp on conflict, and no wonder. Those problems, challenges, obstacles, and inner struggles help keep readers engaged, casting doubt on the character’s ability to achieve their goal.

Because readers are focused on what’s happening from one scene to the next, it can appear that conflict is only occurring moment to moment. It’s actually present at different levels in the story, not just at the scene level. Understanding the levels of conflict and how various challenges will interact is key to building a rich, powerful story, so let’s dive in.

Level 1: Central Conflict

Every story will have an overarching conflict that should be resolved by the end of the book. Whether your protagonist is trying to prevent evil creatures from entering their world (Stranger Things), stop the terrorists who have taken over Nakatomi Tower (Die Hard), or find the groom and get him to his wedding on time (The Hangover), they must address that problem. The central conflict for any story will take one of six forms:

- Character vs. Character: The protagonist goes up against another character in a battle of wits, will, and strength.

- Character vs. Society: The protagonist takes on society or an agency within it to bring about necessary change.

- Character vs. Nature: The protagonist battles a form of nature, such as the weather, a challenging landscape, or its animal inhabitants.

- Character vs. Technology: The protagonist faces a manufactured foe, such as a computer or machine.

- Character vs. Supernatural: The protagonist confronts a force that exists outside their full understanding. This may involve an encounter with fate, a god, or some other magical or spiritual foe.

- Character vs. Self: The protagonist experiences a large-scale internal battle of clashing beliefs, hopes, needs, or fears.

The central conflict locks the wheels of your story’s rollercoaster onto a specific track so the macro and micro challenges you add will support plot and character development.

Level 2: Story-Level (Macro) Conflict

Some conflicts present bigger problems that your character doesn’t have the means or ability to solve. These threats loom over much of the story, and the protagonist will have to work through them while handling other immediate, scene-level dangers and challenges.

Do you know the 4 levels of conflict in storytelling? @AngelaAckerman shares the details Click To TweetFor example, in Die Hard, John McClane is one man against an organized, armed group who have taken over Nakatomi Tower. His central conflict (character vs. character) is to stop the terrorists and save everyone in the building, especially his wife. That on its own seems impossible, but it’s complicated by a few other problems he also must deal with: keeping Holly’s identity as his wife a secret so the terrorists can’t use her as leverage, figuring out Hans Gruber’s real motive for taking over the tower, and doing it all despite the bungling interference of a grossly inept FBI.

And in the back of his mind is the most challenging problem of all, the one that brought him to California in the first place: how to fix his crumbling marriage and reconcile with Holly before it’s too late.

Large-scale conflicts like these will need to be addressed by your protagonist, but they won’t be ironed out immediately. Very often, the character will have to work on these issues in stages as they dodge danger and achieve smaller goals from scene to scene.

Level 3: Scene-Level (Micro) Conflict

Conflict at the scene level comes in the form of as-it-happens clashes, threats, obstacles, and challenges that get between your character and their goal. The character is trying to handle what’s right in front of them, deal with inner struggles, and above all else, prevent disaster.

Sometimes they succeed and sometimes they fail—and failure is part of the process, by the way. Setbacks are necessary to increase the pressure, introduce complications, raise the stakes, and force your character to examine why things went wrong. This last one is especially important for characters on a change arc since internal growth is crucial for them to successfully achieve their story goal.

In Die Hard, John McClane pulls the fire alarm so first responders will arrive and discover what’s going on in the tower. This fails when the terrorists convince the fire department it was a false alarm. Worse, it places a target on John’s back because now Hans Gruber and his mercenaries know that someone in the building is working against them. A manhunt results with John, unarmed and barefoot, fighting to stay a step ahead in each scene by outwitting, overpowering, and killing those sent to eliminate him.

Level 4: Internal Conflict

Another form of conflict takes place within the character. At the macro level, it’s the main internal struggle the protagonist must address to achieve their story goal.

Ever wonder how we can include conflict on every page? @AngelaAckerman shares the 4 layers of conflict we can draw from Click To TweetJohn McClane’s marriage is a breath away from breaking because he’s self-absorbed and unaccommodating, believing his needs and career should come first. Holly, rather than become a minimized puzzle piece in John’s world, moves herself and their children across the country to follow her own professional dream. John visits her with the goal of reconciling, but he’s really hoping that her choices have shown her she’s better off in New York with him. Instead, he finds her happy, thriving in her career, and independent—so independent, she’s using her maiden name.

This ego hit makes John realize that getting her back won’t be easy, and if he wants to make it work, he might have to make some sacrifices. This sets the stage for his inner conflict—putting himself or others first. With Holly in mortal danger, he realizes how selfish and unsupportive he’s been and wants the chance to tell her so. This awakening is John’s first step toward resolving his inner conflict, which he achieves when he does everything within his power to stop Hans and protect Holly, no matter what the personal cost.

Internal conflict also happens at the micro level with conflicts arising in individual scenes. Faced with the crushing force of painful circumstances, pressure, and opposition, characters often struggle with what to do, knowing right from wrong, and even what they should feel. Conflicting emotions and competing desires, needs, and fears can paralyze a character, cloud their judgment, and make decisions and choices that much harder.

Conflict Powers Our Story

External or internal, macro or micro, conflict powers your story.

It pushes and pressures the character, stands in the way of his greatest desire, and strains him to his limits, making him want to quit. Then he’ll have to show his strength and prove his worthiness by fighting, making sacrifices, and being willing to change to achieve his goal.

Encourage Uneven Matchups

As you’re strategizing ways to use the four levels of conflict in your story, look for opportunities to highlight inequities. When we engineer story elements to be unbalanced, it generates immediate friction by putting the protagonist at a disadvantage. Let’s return to Die Hard and look at some of the disparities.

How can we make our story's conflict as powerful as possible? @AngelaAckerman shares her tips! Click To TweetAt first glance, John’s experience as a seasoned New York police officer seems like he has the skills to deal with a threat like Hans Gruber. Only…Hans isn’t alone, and John is unarmed and in an unfamiliar place. Worse, when the building is taken over, he’s trapped with no leverage or resources—not even a pair of shoes. Hans, on the other hand, has a team of skilled and well-armed mercenaries with full building access and plenty of hostages, including John’s wife.

This imbalance makes stopping Hans and protecting Holly seem futile, and for much of the movie, John’s goal is out of reach. But his inventiveness at handling conflict at the scene level—taking out his enemies one by one, dropping a dead body on a car to draw a policeman’s attention, getting his hands on a weapon, and stealing Hans’ detonators—allows him to balance the scales.

Winning becomes possible. His actions when dealing with conflict also give readers a chance to see who he really is!

*****

Want your conflict to go further?

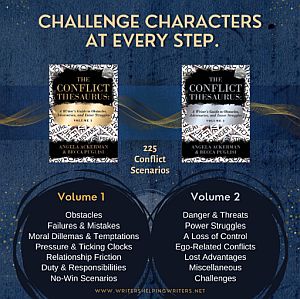

The Conflict Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Obstacles, Adversaries, and Inner Struggles (Volume 1 & Volume 2) explores a whopping 225 conflict scenarios that force your character to navigate power struggles, lost advantages, dangers, threats, moral dilemmas, ticking clocks, failures & mistakes, and much more!

Brainstorm the perfect story problem or challenge for your characters, pushing them to adapt and bring their A-game if they are to achieve their goal.

*****

Angela Ackerman is a writing coach, international speaker, and co-author of The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Expression and its many sequels. Her bestselling writing guides are available in ten languages, and are sourced by universities, recommended by agents and editors, and used by writers around the world.

Angela is also the co-founder of the popular site Writers Helping Writers, as well as One Stop for Writers, a portal to game-changing tools and resources that enable writers to craft powerful fiction. Find her on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

*****

Thank you so much, Angela! This post is a fantastic summary of the different types of conflict and how they work together to create the tension on every page that keeps our readers turning pages. I also love the Die Hard example and how you pointed out how his choices when facing the story’s conflict help us understand his character and root for his success.

We might have a grasp of the big, story-sized conflict determined by the central storyline of our premise. Or we might comprehend the story-sized conflicts of our subplots and other major character goals. Or maybe we understand the scene-level conflict of obstacles. Or perhaps we’re able to wield internal conflict. But it’s important to see how all the different levels of conflict work together to create a greater sense of progress and tension—and storytelling—throughout our story.

When we fully understand what all goes into our story’s conflict, we better understand how yes, tension from at least one level of conflict exists on every page. With that understanding, we can ensure every page of our story is working to keep our readers engaged and turning those pages. *smile*

Have you ever struggled with the advice of “ensure every page includes conflict”? Have you ever thought about the different levels of conflict our story contains? Does seeing these different levels all summarized and explained here help you see how they work together to strengthen our story? Do you have any questions for Angela?

I don’t think conflict is necessary on every page – at some point, those conflicts, especially between characters and inner conflict, can get resolved. (Notice I didn’t say have to get resolved 😉 ) Especially when inter-character conflicts lead to inner conflicts, which are then resolved so the inter-character conflict can be resolved. I don’t think resolutions should be “Oh all is well, let’s frolic through the daisies” either, But they can be acknowledging a common goal and working together to get there. JMHO, but constant conflict can be exhausting for both writer and reader.

Hi Star, I think where the waters grow muddy is when we equate conflict to only being something big and explosive that happens in a scene, like a monster hunting the character or a car bomb hidden in their Camaro. But if we think about conflict as “unresolved problems,” I think it’s fair to say most scenes will have conflict. For example, until the climax’s outcome, the character will be trying to solve the central conflict (problem). If you consider Mitch (Tom Cruise) in The Firm, he’s trying to avoid being killed &/or jail because the law firm he works for is corrupt. But he’s also got other big problems (like how to save his marriage after revealing he’s cheated on his wife). These conflicts are in the background, unresolved, for most of the movie. Scene to scene, there’s also plenty of conflict – the danger of playing both sides, the lies that must be told convincingly, blackmail, having to collect evidence and not get caught, his house, car, and office being bugged, etc. And then finally there’s the inner conflict going on within Mitch – what to do when the career he’s worked for so hard for is going to be taken from him, the guilt of cheating, disillusionment and frustration at being asked to behave unethically, feeling responsible for another’s death, etc. As long as any of these are present, there’s conflict, even if it’s those yet-to-be-solved problems in the background. The exception though would be the dénouement.… — Read More »

Yeah, I wasn’t thinking about “explosions” re: conflict, but those unresolved problems that usually, at some point, get resolved. It doesn’t have to happen at the end of the story – there are many small conflicts throughout a story that can be resolved within the story – and that offers more opportunities to not only move the story forward but change the dynamics between characters (and thus an opportunity for different conflicts between different characters).

Yes, exactly. It keeps the story fresh that conflicts are resolved along the way and new ones are born until finally the character succeeds (or doesn’t) and either way, the main story is complete:)

Thank you very much for this. Published advice does not write some rules for writers in plain English. Some ironclad rules I found stated EVERY scene has to have a conflict incident, a crisis, and resolution, and a charge of state to the character. Examples included one from a children’s book where the crisis was much less dramatic than I would ever label a crisis. The rules are helpful, but you need to think commonsensically about them. I think a crisis per scene requires plenty of work without trying for a crisis per page. Writing is fun, but it sure can be hard. (I doubt if I’m the first to discover this.)

Hi Michael,

Ugh, yes, I don’t go for those kinds of rules, as every story — and every author’s intention for the kind of story they want to tell — is different.

What’s important to recognize here is that having conflict on every page doesn’t mean that conflict is explicitly shown, and certainly not including a full-blown crisis that’s changed or resolved within a page, or even a scene.

So saying that conflict belongs on every page doesn’t mean that we’re introducing new conflict every page, or that we’re showing a whole conflict arc, or that it has to be explicitly shown and active, or anything else like that. It simply means that we’re ensuring that conflict in some shape or form (showing, telling, subtext, allusion, etc.) is at least a layer over whatever is going on for that page.

Hope that helps and good luck with your writing!

Great explanation, Jami!

Thank you both to Angela and Jami. While I complain about the rules, I am so glad I’m learning them now while I can still revise my work before asking an expert to read it. I’ve paid for two professional critiques in October and I don’t want to submit samples that show my ignorance of basic rules for keeping my story moving. I appreciate your advice.

It’s so true. And I think the more we learn about how everything works together, the more we realize just how complicated it is. But that’s why we have revision! 🙂

This is great information! Thank you!!

Very glad it helps, Apryl!

Thanks for sharing this information. I’m so pleased to have read it.

I agree that this is good advice, but I suspect it depends upon the genre. I have seen this conflict style used to advantageous effect in thrillers, fantasy, and many other genres but cannot imagine it applies across the board. I have read many ghost stories, for example where the style is building suspense. Hard sci-fi (Imagine Iain M banks describing five-dimensional thought in mathematical terms for five chapters with this in mind. Literary fiction, Herman Hesse describing a cloud (for pages and pages). But on the whole, dependent upon genre, it is great advice. I intend to follow it in full when I write my next cook book. Kidding. Though that might be fun…….Onions or carrots first he thought with a soul-searching intensity, the sharp paring knife clutched desperately in his right fist, there could be blood as he tried to set the timer. No time to drop the knife, the water should be boiling, the pinch of coriander mesmerizing, the aroma cutting the steam and perhaps his finger if he sneezes. A sip of red wine and a cupful for the meal, Incipient cirrhosis takes his mind to the red wine. His wife enters and opens the windows “The steam in here, you will cause condensation, the wood will rot and the house fall down around our ears”. The kitchen starts to clear but will it be quick enough for him to notice the errant slice of red pepper that fell to the tiled floor before he put… — Read More »

Hi Raymond,

Yes, how the specifics of any piece of advice applies always depends on genre, as well as our goals for the type of story we want to tell.

Some genres and stories focus more on one level of conflict or another. I’ve even written before about a non-Western-storytelling view of conflict that approaches the idea from a completely different perspective. Thanks for chiming in with your entertaining cookbook example! 🙂

[…] yourself with the varying levels of conflict and how to layer them into a story to make it rich, powerful, and […]