How Can We Worldbuild on an Epic Scale?

Early last year, I explored whether we could worldbuild without a plan. At the time, my perspective was mostly focused on pantsers, those who write by the seat of their pants and don’t plot in advance.

However, no matter how we write, it’s good for us to develop this worldbuilding-on-the-fly skill, as every story requires us to build a story world (at the very least for the genre, setting, and culture: think of small-town cozy mysteries vs. big-city political thrillers). And at the same time, there are many reasons we might not be able to plan every detail of our story world ahead of time.

For example, in addition to simply being a pantser, we might want to expand a successful standalone story into a series after the fact to take advantage of its popularity. Or we might want to create a spinoff series related to an existing one. Or we might want to play with other authors in a “shared world” series.

Worldbuilding in a piecemeal way can work—and work well. In fact, the approach can create an epic story world that readers love to explore.

How can we make this style of worldbuilding work for us? Let’s take a deeper look at the process of worldbuilding in pieces: How can we build a cohesive epic-sized story world, even if we don’t plan everything in advance?

Can Piecemeal Worldbuilding Really Work?

While many point to the Marvel Cinematic Universe as an example of building a story world a bit at a time, the Marvel movies never acknowledge events from Marvel’s TV shows or publishing efforts, leading to the impression that they’re taking place in alternate universes. So that’s not going to be my focus today.

In contrast, the Star Wars universe’s canon includes not just the movies, but also TV shows and publishing. The Star Wars movies often incorporate characters, events, and worldbuilding details from the canon TV shows The Clone Wars and Rebels. The world of the movies includes references to details from canon books and comics as well.

For the most part, the Star Wars canon universe works together to build a cohesive, epic-scaled whole. That’s quite an achievement.

Think about it: Any amount of consistency is surprising, given that even the core movies (much less the various TV and publishing efforts) were created out of chronological order and by multiple developers. In other words, the Star Wars universe shows that piecemeal, nonlinear worldbuilding can be done successfully.

Why Look at Piecemeal Worldbuilding?

I started thinking about how writers could benefit from understanding piecemeal worldbuilding when—with my recent frustrating health issues—I had to cut back on my activities. (All my various prescribed medications have caused more problems with their side effects, and that’s one reason why my posts here have been so infrequent recently. *sigh*)

Between my health struggles and the pandemic, like many people, my family has been spending a good chunk of our time bingeing movies and shows, catching up and exploring things we missed. Also, like many Star Wars fans, we’re eagerly awaiting the second season of the “Baby Yoda” show, er, The Mandalorian.

So several months ago, we decided to binge the Star Wars canon in chronological order up to when The Mandalorian takes place, before the episodes of the new season start dropping on Disney+ this Friday. In addition to rewatching the obvious movies, we’ve also been reading some of the novels and watching The Clone Wars (7 seasons) and Rebels shows (4 seasons), which we hadn’t seen before other than just a few random episodes here and there.

Want to build an epic-sized story world? Here's how a game and Star Wars might be able to help… Click To TweetDespite how the TV shows could have been just shallow kids cartoons—merely showing what happened during the Clone Wars between the movies’ Episodes 2 and 3 or during the start of the Rebel Alliance between Episodes 3 and 4—they end up deeper and more emotionally powerful than the movies. For example, The Clone Wars doesn’t flinch from exploring the morals of using clones as cannon fodder to fight a war, and it does a far better job of examining Anakin Skywalker’s behaviors and choices, both good and bad.

In other words, the non-movie parts of the canon don’t just add details for the sake of details, but they make the movies and the whole storyworld better. In particular, the final arc of The Clone Wars is beyond-words amazing, as it makes the Order 66 extermination of the Jedis in the movies’ Episode 3 more meaningful and heartbreaking.

(In fact, that arc is now my favorite two-ish hours of Star Wars ever. And yes, I’m old enough that I saw the original Star Wars movie in the theater (before it was re-titled A New Hope) and later skipped school to see Return of the Jedi opening day. So for an animated story to overtake my love of the movies really means something. *grin*)

As an author (and one who writes by the seat of her pants), I found the piecemeal-yet-cohesive worldbuilding of the Star Wars universe fascinating, especially seeing how each piece added to the whole and made events in other stories more powerful too. So I wanted to explore what we, as writers, could learn from a deeper look.

What Is Nonlinear Worldbuilding?

As I mentioned above, the Star Wars universe was built out of chronological order. Most obviously, Episodes 1-3 of the movies were made after Episodes 4-6. But the rest of the canon was created in random order as well.

How can we build a story world for a series without planning everything in advance? Click To TweetEven within The Clone Wars TV show, the episodes don’t follow chronological order. For a single story arc, the creators often made one episode about an event, but the episode “introducing” the characters for that event wasn’t written and produced until the next season. And then the episode showing the immediate fallout of that event might not have been released until the season following that.

(Suffice it to say that I wouldn’t recommend watching the show in release order but rather in chronological order. We followed the “ultimate” episode order to include the Forces of Destiny shorts and just ignored all the stuff about comics and Legends (non-canon) books.)

Watching the series in release order would lose all the continuity built into the worldbuilding and story arcs. But the fact that there was continuity, despite the episodes being written and produced in random order, just goes to show how nonlinear worldbuilding can be done successfully.

Some writers draft their stories in nonlinear order as well, writing scenes as they feel like it, and only later assembling them into the proper sequence. This worldbuilding approach is similar, as it involves keeping track of various story and worldbuilding threads.

Sound Confusing? Here’s Another Example

Like many others, another activity my family has enjoyed during the pandemic is playing games, but we often try out unusual ones that most have never heard of. One game that made an impression on us is called Microscope.

The game of Microscope is hard to describe, but it’s designed to allow you to develop a world’s history, even hundreds or thousands of years long, all in just a few hours. The beauty of the game, however, (and what really caught my attention for this topic) is that you don’t design the world in chronological order.

“You can defy the limits of time and space, jumping backward or forward to explore the parts of the history that interest you. Want to leap a thousand years into the future and see how an institution shaped society? Want to jump back to the childhood of the king you just saw assassinated and find out what made him such a hated ruler? That’s normal in Microscope.

You have vast power to create… and to destroy. Build beautiful, tranquil jewels of civilization and then consume them with nuclear fire. Zoom out to watch the majestic tide of history wash across empires, then zoom in and explore the lives of the people who endured it.”

While groups (including a shared-world author group) can play the game to let everyone’s different ideas come together to form a cohesive whole, it’s also possible for a single author to use the framework of the game to build a story world. Let’s take a look…

Worldbuilding with the Microscope Framework

Playing the game of Microscope helped me see how we can focus on both the big picture and the day-to-day details of a story world, and more importantly, how worldbuilding doesn’t have to be a linear exercise, even from book to book or story to story. Like the writers in the Star Wars universe, we can jump wherever we want in our story world’s timeline to explore the reasons and/or fallout of events and character actions or the ties and influences between our story ideas.

Obviously, that can be confusing and lead to inconsistences if we’re not careful. But I’m going to explain the gameplay of Microscope a bit to demonstrate how a framework for our world can help keep us in line.

Step One: Big Picture

Brainstorm the type of story world you want. In writer terms, this means come up with a basic premise for our world.

Is the world…:

- the hellscape of the high school years?

- populated by superheroes or fantastical creatures?

- about refugees exploring the vastness of space for a new world?

In the Microscope game we played, we decided on a world where civilization rose and fell again and again, as the population didn’t learn from their mistakes. In the Star Wars universe, the story world spans a galaxy that includes both technology and magic.

Step Two: Ban or Integrate Certain Elements

Next, you’d decide what elements you definitely want or don’t want in your story world. Do you want to ban magic or anything supernatural? Do you want to focus on politics? Do you want to explore lots of shades of gray within individuals?

How can a game help us build a nonlinear story world? Click To TweetWhen playing as a group, each player gets to add at least one thing to the Yes or No list. Players also get to negotiate the list, so everyone agrees on what big-picture aspects are acceptable or not.

In the game we played, we decided there would be no “chosen one” characters, no evil religion or outside influences causing problems, and no written language. In the Yes column, I added dragons (and that they were noble creatures) because…paranormal author with a shapeshifting-dragon story here. *grin*

Others decided that pancakes (yes, pancakes!) were an important part of the civilization’s culture and that fraying cultural norms and common values were a problem. (In other words, anything goes here, but the idea is to make sure that everyone is working with the same storyworld “rules.” However, if we’re “playing” by ourselves to develop our own story, this is where we’d think about what we want the heart of our story to be.)

In the Star Wars universe, the rules would include things like how the Force is real and allows for magic-like effects, but can also be used for good or bad. Anything not specifically on the No list is fair game, including things like Force-wielders beyond the traditional Jedi and Sith.

Step Three: Bookend History

Decide where you want the exploration of the world to start and stop. The span of time here might be anything from a year to millennia. The purpose of this step is understanding that every event has a cause and an effect, and we need to stop following the chain somewhere.

In the game we played, we started with the world’s first fall, as the population began to delve into dark magic. We ended with the world’s second fall, as the survivors’ new civilization failed to learn from the mistakes of their predecessors.

In the Star Wars universe, the bookends most of us are familiar with would be along the lines of the rise and fall of Palpatine, with his election to Chancellor in Episode 1 and his eventual (permanent?) second death in Episode 9. That said, the Star Wars scope can be easily expanded to include stories from earlier in the Republic or later after Episode 9.

Step Four (A): Fill In the Blanks

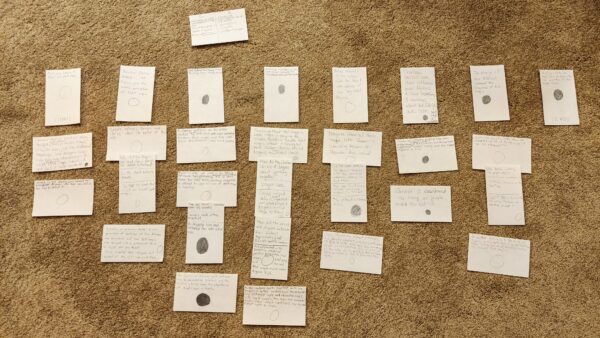

In an official game of Microscope, once these guidelines are established by the group, each player now gets to develop their own ideas for Periods, Events, and Scenes. (The gameplay uses normal index cards to write each of these ideas.)

- Periods are big in scope and are placed horizontally in a line between the bookends.

“The civilization crumbles as dark magic consumes the land around them and their minds.” - Events are smaller (like a turning point in the big picture) and are placed vertically under a Period with a horizontal card.

“Realizing that the dragons were right about the risk of dark magic, clerics ally with the dragons to try to prevent chaos.” - Scenes let the group role play to discover an answer to a specific question and are placed vertically under an Event.

“Q: How do the clerics and dragons start working together?

A: Clerics helped defend the dragons against dark-magic-corrupted hordes, and the dragons invited them to stay and survive the coming apocalypse.”

Each player takes a turn being the Lens, deciding what the Focus of the round will be. The Focus can be anything: a location (the capital city), a certain character (the life and teachings of an influential cleric), a thing (pancakes), a problem (dark magic), etc. The purpose of the Focus is to help develop ideas in a coherent way, as once an idea is written, it can’t be contradicted.

(From a writer’s perspective, if we’re following this framework to develop just a single story, we might have a Period for each major plot point (the heroine decides to confront the villain). Events would connect to that plot point (the heroine goes to the villain’s lair), and Scenes ask questions connected to the Event (Does the heroine successfully corner the villain?).)

Step Four (B): Connect the Dots

For each Focus idea, every player creates Periods, Events, or Scenes anywhere in the timeline and marks each one as positive or negative for the world (with an empty or filled in circle). In this way, the world is developed with story threads in two directions:

- Vertically: Delving deeper into an idea in a single Period of time

(See the examples in the bullet points above.) - Horizontally: Exploring the connections and previous causes or later effects of any idea over the entire world’s scope

(How would long-lived dragons who give the populace advice affect a civilization without written language…and what would happen to the population without that advice after the dragons sacrifice themselves to cleanse the land of dark magic?)

In the Star Wars universe, The Clone Wars TV show was bookended by Episodes 2 and 3 of the movies to create a (wide) vertical thread. Within that time frame, the writers jumped around chronologically from released episode to episode, but eventually delved into the events of each idea to create complete story arcs.

Then throughout the rest of the canon, the ideas explored in the series continue as horizontal threads, with characters and story arcs showing up in later ideas like the Rebels show and Rogue One and Solo movies. Rumors are that at least two characters from The Clone Wars will be showing up in The Mandalorian, and as long as the character introductions are handled well enough to not confuse unfamiliar viewers, connected details like that help build a more cohesive world.

Worldbuilding Tips from Microscope

Now let’s pull out the important points of the game to see if it helps us come up with some worldbuilding tips for our writing.

- Decide on the type of story world you want.

- Decide what elements you definitely want to include or exclude.

- Decide the scope of the story world and its relevant history.

- Explore big picture, medium picture, and small picture details that interest you within the scope.

- Ensure that details don’t contradict earlier details or include excluded elements.

- See how details are related or connected both vertically (within a single time focus) and horizontally (across the cause and effect chain of time).

- Explore each idea to the world’s satisfaction… Eventually. *grin*

Final Thoughts

In other words, if we struggle to follow story threads or understand how they relate… Or if we struggle to see both a storyworld’s big picture and small details without twisting our brain into knots… Then we might benefit from playing this game.

Microscope is so unusual that it might take a bit to really grasp how to play (even though the rules are actually quite simple). However, once we get it, it’s easier to see how a storyworld’s threads relate and influence each other, both into the past and the future.

With that skill, we can make worldbuilding details we come up with later fit with other ideas we’ve already had. We can build a cohesive world that adds meaning and epic scope with each event we develop. *smile*

What story worlds have you come across that feel epic and/or cohesive to you? Were they developed all at once or piecemeal/nonlinearly? Have you struggled to worldbuild in your stories? Do you find it difficult to keep worldbuilding details consistent and cohesive, especially with nonlinear development? Do you have any questions about worldbuilding, or does this post give you any ideas?

Pin It

Hi! I played Microscope this past weekend with some friends and it was an incredible experience. It’s fascinating to take a “god’s eye” view of a world/universe/country/whatever and determine its complete history. What’s even better is that I can see this being used to create a whole series of books or short stories that reside within the totality of that history. I recommend Microscope to anyone who enjoys story building with others.

Hi April,

Awesome! I’m glad I’m not the only one who saw the possibilities. 🙂

And yes, I thought the same thing with the game we played, as almost every card could have been turned into a book–at least as a short story–for a whole series or multiple connected series. That’s what got me thinking about this post. 😉 Thanks for sharing!

With two authors and one game designer playing, it was *hard* not to see the possibilities! There were more than a few moments of “that would be a cool story” or “I want to write that”.

Oh yes! What a fun group to play with. 😀

[…] captures your reader’s imagination. Jami Gold reveals how to worldbuild piecemeal, Stephanie Kane discusses writing about the unfamiliar, Stavros Halvatzis explores how location […]

[…] How Can We Worldbuild on an Epic Scale? by Jami Gold […]