Story Elements: Give Them Purpose

Last time, I talked about how we can ensure our pacing is “good.” As I went into further in my guest post at Writers Helping Writers, one way to make sure our story’s pacing is strong is to ensure every element has purpose.

How can we do that? As Dawn asked in the comments of my guest post:

“How do I know if a scene is pointless? What questions should I be asking myself about whether certain paragraphs or sentences have purpose?”

Let’s dig into what we can do to ensure every element has a purpose…

Scenes vs. Smaller Elements

Let’s start by acknowledging that a pointless scene is different from, say, a pointless exchange of dialogue. They both can hurt pacing, of course, but the size of the effect is different.

Obviously, a scene is a bigger chunk of the overall story than a few paragraphs. Likewise, a scene without a purpose will be more noticeable to readers than a smaller element, whether a word, sentence, paragraph, or section of a scene.

That said, the cumulative effect of smaller elements without a purpose can add up to have a larger effect as well. A single repetitive adverb isn’t a big deal. Dozens or hundreds of them over a whole story—especially if other types of extra and/or unnecessary words also litter our story—can have an out-sized effect, even if readers can’t point to a specific reason for the pacing feeling sluggish.

Finding Pointless Scenes

As scenes have the biggest effect on our stories, let’s focus on them first. How can we figure out if our scenes have a purpose?

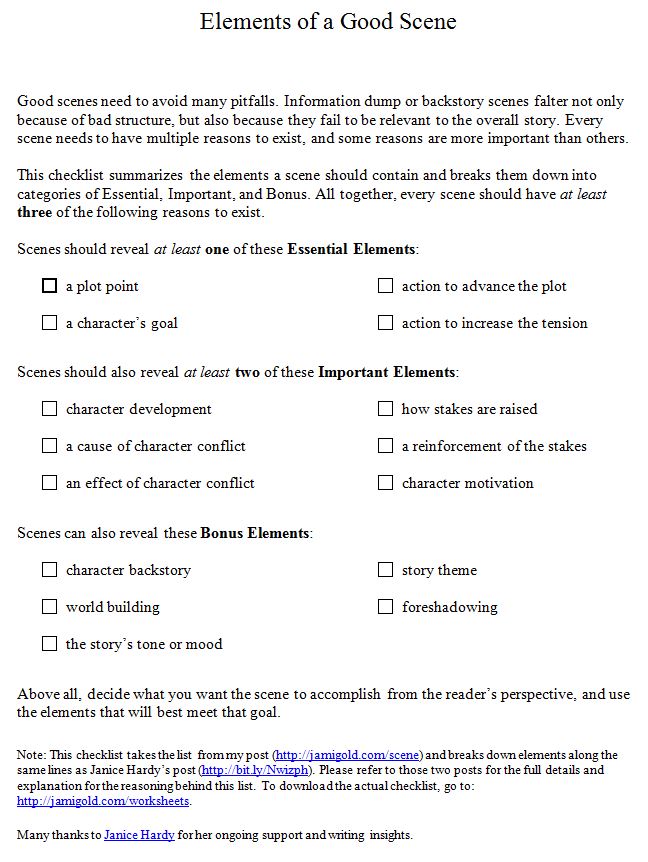

Luckily, I’ve already written a post (and created a checklist/worksheet!) to answer this question. *grin* As I said in that post, good scenes should have at least three reasons for existing.

In addition, at least one of those reasons should reveal an essential element, such as a plot point, a character’s goal, action to advance the plot, or action to increase the tension. (To check multiple scenes, my Elements of a Good Scene Worksheet might be more helpful than the Checklist below.)

- Click to download the Elements of a Good Scene Overview – MS Word ’07/10 Version (.docx) by Jami Gold

- Click to download the Elements of a Scene Overview – MS Word earlier version (.doc) by Jami Gold

Digging Deeper into Scenes

Beyond even the worksheet, the most important question we can ask ourselves about our scenes is:

“What do we want this scene to accomplish from the reader’s perspective?”

Most problems with pointless scenes are due to us following the flow of ideas while we draft our story, but not really having a goal in mind for what we want the scene to accomplish. Once we know what we want a scene to accomplish, we can then figure out the best way to use the scene to accomplish that goal.

How can we dig deep into our story to ensure every element exists for a reason? Click To TweetMaybe we’ll decide the words of the dialogue are revealing the right information, but the tone is wrong. Or maybe we’ll decide there’s a better way to show the protagonist’s vulnerability. Or maybe we’ll decide we let the protagonist advance the plot too easily. Etc., etc.

We might also need to analyze whether our tangents and subplots have a purpose or if they’re pointless as well. We should ask ourselves whether they’re meaningful or if they’re a distraction from the story.

What If Our Scene Is Pointless?

What if we discover a scene without a purpose? What can we do with it?

As I’ve talked about before, it’s okay to occasionally have story elements that don’t immediately tie together. Sometimes we need a random event to trigger the next part of the cause-and-effect chain of our story.

However, every scene should have a purpose that eventually becomes apparent. If—even after we’ve drafted the whole story—we can’t point to what we’re trying to accomplish with a scene, we need to make a choice:

- We can change our story or plot to give our scene a purpose.

For example: In a scene of cute banter between our characters, we can add a reveal of plot information to the conversation or use the conversation to trigger and reveal a change to a character’s goal, etc. - We can trim our scene to be short enough to add to another scene that already has a point.

For example: In that cute banter scene, we could cut all but the best exchanges and then combine that conversation with another scene between the characters that has a solid purpose already. - We can cut the scene.

For example: We could cut the whole scene but save it for a bonus scene for our website or newsletter for readers.

What Can We Do for Smaller Story Elements?

Now that we understand how to find, analyze, and fix big scenes without a purpose, can that knowledge help us with smaller story elements too?

Let’s go back to that most-important question listed above:

“What do we want this scene to accomplish from the reader’s perspective?”

This same question—slightly modified—can help us with every element of our story, from a single word to a sentence or paragraph:

“What do we want this element to accomplish from the reader’s perspective?”

And again: Once we know what we want an element to accomplish, we can then figure out the best way to use the element to accomplish that goal.

If that adverb is doing exactly what we want, we get to keep it. Same with any sentence or paragraph or section. If the element is fulfilling the what and how we want for readers, it has a purpose in our story.

What Reasons Are “Valid” Purposes for Smaller Story Elements?

Obviously, not every word and sentence is going to fulfill one of those “essential elements” listed on the Checklist above. So the reasons that can justify the purpose of smaller elements is very different from the reasons we use for scenes.

The reasons listed under “important” and “bonus” on the Checklist are just as valid as those marked “essential.” In addition, we can add other reasons to our list that are valid for smaller elements:

- voice

- subtext

- rhythm

- showing vs. telling

- evoking emotions

- character perspective

- etc.

In other words, we wouldn’t want a whole scene where the main purpose was the “bonus” reason of backstory, but a phrase or sentence of backstory context is often essential for a reader’s understanding. Or sometimes we need to add “extra” information, just to more fully establish our character’s point of view. Those are all valid reasons, and the point is just to make sure we have a reason for including the element.

Want to know if that sentence or paragraph should be cut? Here's how to tell... Click To TweetHowever, as I mentioned in my guest post, there’s no formula that will result in a definitive list of valid purposes for smaller story elements. Our genre, voice, story length, goals for reader connection, and goals for reader experience all change how much leniency we might have in analyzing whether a smaller story element is pointless.

For example, the same sentences that would feel valid in a story with a chatty voice would feel sluggish in a story with a just-the-facts voice. Or an author with a goal of creating a character-focused emotional story could give themselves more leeway on sentences and paragraphs that are designed to evoke emotions than an author with a goal of creating a fast-paced thrill-ride story.

Help! Is There a Short Cut?

Obviously, analyzing every word, sentence, and paragraph at this level would be a ton of hard brain-work. So naturally, we’d like to know if there are shortcuts we can take advantage of. *smile*

First, we can learn our personal struggles with certain elements and pay more attention to those. For example, I almost never get my characters’ introspection paragraphs right the first time.

So I’ve learned to ask the “what am I trying to say/accomplish” question constantly when I’m editing those sections. (I don’t worry too much when drafting.) Once I know what ideas, thoughts, and emotions I’m trying to get across to readers, I often rewrite the whole paragraph(s) or section to fit.

Second, as we edit and/or get feedback, we can pay more attention to sections that feel “off.” If a scene feels sluggish, we can look deeper at each sentence and paragraph, checking for unnecessary words, pointless sentences, etc. If a section feels choppy, we can think about if there’s a better way to express the idea, such as adding more transitional context to explain motivations or thoughts.

Then if we find ourselves having to correct the same types of elements frequently—such as dialogue, descriptions, action scenes, introspection, transitions, etc.—we can add that element to our list at step one. With practice, we’ll improve and be more efficient with when we dig deep into analyzing our story elements. *smile*

How much do you analyze your writing for whether elements have a purpose? Do you struggle with knowing how to do that analysis? Does this post help explain how to take that step? Can you think of other insights about valid reasons or shortcut techniques? Do you have any other questions about how to figure out if our story elements have a purpose?

P.S. If you missed my post last week, check out how you can donate to a great literacy cause and receive a signed book of mine in thanks!

Pin It

Thank you for this! Last month I spent two weeks on a single chapter. I knew it sucked but I didn’t know what to do to fix it. I reworked it several times and nothing helped. Either my subconscious or some higher power stepped in because when I went back to it another day, it was gone. Somehow, I accidentally deleted it. And I don’t regret it one bit. Maybe next time I can save time by using your elements of a good scene checklist to either fix or delete things I know aren’t working.

Hi Dawn,

Yay! So glad you found this helpful. 🙂

And yes, as I mentioned in the post, I don’t do this in-depth analysis unless I have an inkling from instinct or feedback that something’s off. Hopefully that helps you too. 🙂 Thanks so much for the great question!

Thanks Jami. My mum once told me I had unnecessary scenes because they didn’t advance the plot. I said they were needed to demonstrate character. Showing rather than just telling the reader how this character would behave, so later their actions were no surprise.

I don’t have scenes that aren’t useful in a mystery, particularly. Everything needs to be tightly planned in a mystery, even if you’re a pantser.

Hi Clare,

Exactly! It’s great to advance the plot in every scene if we can, but there are other essential justifications that make scenes without plot advancement valid too. And you’re very right about how mysteries need more planning than other genres. Thanks for sharing! 🙂