Building a Story: Chapters vs. Scenes

We’ve talked before about how there’s no wrong way to get to “The End” when drafting and editing our book. All that matters is whether the finished story is compelling or enjoyable for readers.

We might…:

- write by the seat of our pants

- plot everything in advance

- fall somewhere in the middle between plotting and pantsing

- break down story ideas into scene-by-scene notecards

- write the story linearly or chronologically

- jump around in our draft

Any and all of those techniques can work. And no matter what, successful stories can be the result.

Recently, a Twitter conversation reminded me of another variation for how we write and draft. Some writers think about chapters as they write, and some think about scenes.

The replies to the first tweet in the conversation revealed that plenty of us might not have thought about that difference — and thus we might not have thought about whether the other way might work better for us. So let’s explore our options for building a story and whether our brains work best with chapters or scenes. *smile*

Recap: What Is a Scene?

Many of the disagreements and confusion in writing advice can be chalked up to using different definitions. If we’re the type to build stories by chapter, we might even use the words chapter and scene interchangeably.

As we discovered in our exploration of scenes and sequels here last month, it can be surprisingly difficult to define the word scene, especially if we think of the traditional “change of time” or “change of place” markers, which aren’t always a good fit for how we actually write:

“The understanding of a scene that works best for me is to think of each scene as a mini-story. Each scene has a goal, conflict/obstacles, and some sort of “resolution”—which is often a reaction, a pivot to a new goal, a new epiphany or priority or worry or vow, etc. The end of the scene brings everything together, just as a story’s resolution illuminates the point of the story.

So for me, a scene is more about feeling emotionally complete from that mini-story perspective. It feels like it’s fulfilling its purpose.”

But Really…What’s the Difference between Scenes and Chapters?

For some reason, many of us seem to have learned to write our stories in chapters. This might be because when we first start on our writing journey, we bring our experience as readers with us.

As readers, we’re more likely to notice chapter breaks than scene breaks:

- Chapter breaks include a page turn and a half-blank page with big font—sometimes even an image.

- Scene breaks (if they don’t line up with a chapter break) might just have a line break (an extra blank line between paragraphs) or a few asterisks or small flourish, with words continuing on the same page.

Movies or TV shows about writers struggling with writer’s block often include a scene with “Chapter One” at the top of a blank typewritten page or computer screen. Voice-overs intone “Chapter One” with the sound of clicking keys when writers get their story idea.

Should we build our story from chapters or scenes? Click To TweetIn other words, in pop culture and newbie thoughts alike, it’s assumed that we write linearly and think in chapter breaks. That’s just considered the “default normal” of writing techniques.

However, that style doesn’t work for every writer. Everyone’s brain is different, and what works for one might not work for another.

Scenes Don’t Have to Line Up with Chapters

As authors, we can each have different approaches to scenes and chapters—even though we all have the same goal of creating a hook at the end of each chapter to get readers to turn that page and keep reading.

- Authors who think in chapters might plan their scenes to line up with the chapter breaks. They might use the rhythm of chapter breaks every X number of pages to determine the length of their scenes.

In other words, for some authors and stories, scene breaks might be the same as chapter breaks, so chapter breaks keep them focused on creating story beats and hooks on a regular schedule. - Authors who think in scenes might focus only on completing each scene. Later, they’ll decide whether each scene is the right length to be a chapter or should carry over from chapter-to-chapter.

In other words, for some authors and stories, scene breaks might fall in the middle of chapters, and chapter breaks might fall in the middle of scenes. Accordingly, chapter-end hooks might come from an emotional moment mid-scene or be a temporary cliffhanger with the reveal on the next page as the scene continues.

What Does It Mean to Build a Story from Scenes?

Between the default normal and our experience as readers, most of us already know how to build a story with chapters. But we might not know how to build a story up from scenes that don’t line up with chapter breaks.

As Preslaysa Williams and Cat Sebastian’s conversation pointed out on Twitter, for some writers’ brains, chapter division can happen late in the drafting/editing process:

I write and revise in scenes. Scene 1, Scene 2, etc.

Turning scenes into chapters is the last step for me. I think chapters are for optics. We are used to them.

The building block of story is the scene. https://t.co/Njrbat3eOv

— Preslaysa *BUY #HealingHannahsHeart TODAY* (@preslaysawrites) September 12, 2019

😂😂😂 Actually, I figured it out after the ONE book that I’ve been working on for NINE YEARS, LOL.

— Preslaysa *BUY #HealingHannahsHeart TODAY* (@preslaysawrites) September 12, 2019

If we’ve never considered our options, understanding the alternative to the default can help us figure out which might work best for us. So let’s take a closer look…

How Do We Turn Random-Length Scenes into Chapters?

Step #1: Draft However It Makes Sense to Us

One of the benefits of building a story up from scenes is that it might be easier than the chapter approach for writers who pants or write non-linearly. With the focus on scenes, we can just tackle one scene at a time in whatever order we wish.

Scrivener is my preferred tool for drafting (even though I’m a linear pantser), as it’s easy to focus on each scene separately. I also tend to edit as I go to some extent, so the ability to jump around from scene to scene allows me to fix things as they occur to me (or at least make a note to fix it later).

In fact, I used to draft by chapter (because that is such the default that I’d never considered another way) until I started using Scrivener. One reason I love Scrivener for drafting is because it helped me realize the benefits of this drafting technique for my brain. *smile*

Step #2: How Long Should a Chapter Be Anyway?

New writers often ask for advice on how long their chapters should be. However, there’s no wrong answer.

Well-known published authors have made stories work with chapters of a single page or line—or stories with no chapter breaks at all. Our voice, story, style, and genre can all play a part on what feels “right” to us.

Just like with paragraphs and paragraph breaks, chapter breaks are a pacing tool and a reflection of our style. We might decide that a 20-page chapter feels like it drags too much or that a 4-page chapter feels too choppy.

Personally, I keep my chapters around 8-10 pages in the typical double-spaced Times New Roman manuscript format. But if needed, I’ll go as short as 4 pages or as long as 12-14 pages.

Step #3: Think about Our Editing Process

Depending on what our editing process is like, it might make sense to figure out chapter breaks right after completing our draft. Or it might be better to wait.

At what point in our writing process should we plan our chapter breaks? Click To TweetIf we tend to cut long sections of our scenes—or maybe even whole scenes—waiting to break our chapters might make the most sense. We wouldn’t want to divide out our story into the chapter lengths we want and then have to redo all the breaks when we make major changes that create too short of chapters.

On the other hand, if we’re a fairly clean drafter, it might not make much difference if we divide our story post-drafting or post-editing. The divisions we come up with should work either way.

Step #4: Check Our Scene Length

Within Scrivener, the scenes in my latest release, Stone-Cold Heart, ranged from 655 words to 4613 words.

- On the short side, that 655 might not be enough to reach my usual 4 page minimum, so I might include that scene at the end or beginning of a chapter with part of another scene.

- On the long side, that 4615 is way too long for a single chapter, so when it’s time to insert my chapter breaks, I skim through the scene and look for places and lines that would make a good hook.

Step #5: Analyze Our Scenes for Hooks

The most important step of the process is looking for hooks to use as chapter breaks. Sometimes those might line up with our scene lengths and their endings and sometimes they might not.

Either way, we want to ensure our chapters end with a hook. Chapter endings should evoke some type of emotion to compel the reader to turn the page rather than put our book down. (Or if they do put our book down because of work or sleep, we want them to pick it back up as soon as they get the chance. *smile*)

Step #6: Add Hooks If Needed

In Stone-Cold Heart, the first several scenes were each around 1200-2600 words, which work well for my typical chapter lengths. So for those, scene breaks equaled chapter breaks.

But the sixth scene was too long—over 3000 words—and in the page or two where it would make sense to break that scene apart, I didn’t have a good hook. No matter. If we can’t find a place or line that would make a good hook, we can add one in editing.

Case Study: How I Go from Scenes to Chapters

Personally, when I’m ready to break my draft into chapters, I transfer my story from Scrivener to MS Word (so it’s easier to get beta reader and editor feedback). Within Word, I switch to a mode where I can see two or more pages at once (such as Read Mode, Print Preview, or View>Side-to-Side), which helps me skim through while counting pages.

For example, let’s look at that sixth scene from Stone-Cold Heart. From one chapter to another, the scene doesn’t change setting, time, or point-of-view. And as I mentioned above, in draft mode, it didn’t have a good hook anywhere close to where I needed one—so in editing, I added one to make a chapter break work for the scene. *grin*

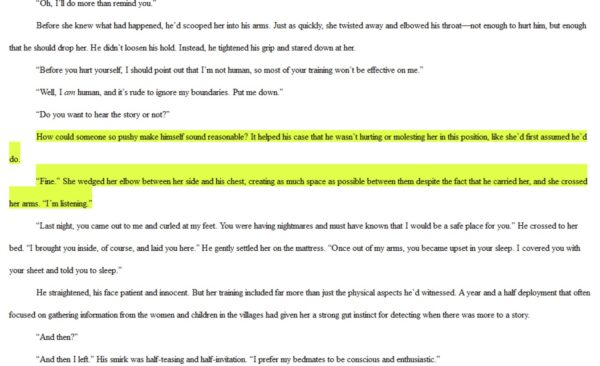

Before the Chapter Break in Scrivener:

In Scrivener, the scene flowed straight through these lines highlighted below:

How could someone so pushy make himself sound reasonable? It helped his case that he wasn’t hurting or molesting her in this position, like she’d first assumed he’d do.

“Fine.” She wedged her elbow between her side and his chest, creating as much space as possible between them despite the fact that he carried her, and she crossed her arms. “I’m listening.”

Original draft in Scrivener without a hook:

(Note: Newsletter readers can click through to the post to view example pictures.)

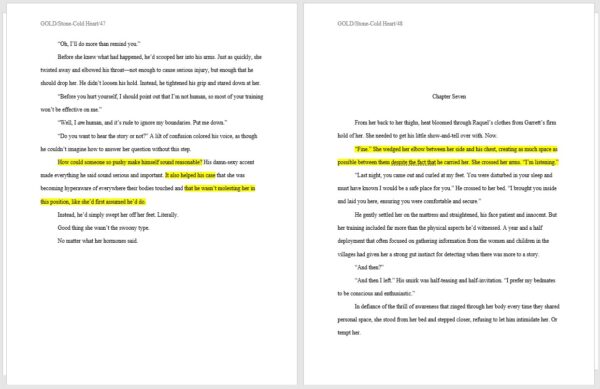

After the Chapter Break in Word:

In Word, the highlighted lines were tweaked to add more sexual tension, insert a chapter hook at the chapter end, and a setting anchor at the beginning of the next chapter:

How could someone so pushy make himself sound reasonable? His damn-sexy accent made everything he said sound serious and important. It also helped his case that she was becoming hyperaware of everywhere their bodies touched and that he wasn’t molesting her in this position, like she’d first assumed he’d do.

Instead, he’d simply swept her off her feet. Literally.

Good thing she wasn’t the swoony type.

No matter what her hormones said.

Chapter Seven

From her back to her thighs, heat bloomed through Raquel’s clothes from Garrett’s firm hold of her. She needed to get his little show-and-tell over with. Now.

“Fine.” She wedged her elbow between her side and his chest, creating as much space as possible between them despite the fact that he carried her. She crossed her arms. “I’m listening.”

Edited version in Word with chapter-end hook:

Why Did I Make That Choice?

For my example above, the new chapter six is 6 pages long and chapter seven is 8 pages long. If I hadn’t created and inserted that new chapter hook and break, the chapter would have been 14 pages, which felt too long to me.

Are there “right” or “wrong” places to break our chapters, or is it an art? Click To TweetWith a different story, voice, genre, or style, 14 pages might be fine. Or a different scene in this same story might be fine at 14 pages as well. I just felt that the flow of this scene was better with the break.

Maybe that’s because adding the chapter hook beat helped the pacing. Or maybe building up more sexual tension created more emotion in that section. Or maybe inserting the chapter break caused a delay in readers just long enough for the emotion or humor of the situation to sink in more. Or, or, or… Or all of the above. *smile*

My point is that no one else can tell us how to approach scenes and chapters. We have to go with what feels right for us and our story.

Determining Chapter Breaks Is an Art

Sometimes, if we’re the type to keep chapter breaks in mind from the beginning, we might get it right on the first try. Other times, especially if we build our stories on scenes and not chapters, we might need to play around with where the breaks work best.

When “chaptering” out my stories’ drafts, sometimes I stick with my first instinct, and sometimes I cut and paste the chapter break formatting into a couple different spots in a scene until it “feels” right. I try not to over-analyze the why behind my choices and just go with my gut.

As I mentioned in my post about scene endings, a strong ending (scene or chapter) can:

- stick with the reader during their break.

- act like the last line of a story.

- help the reader trust the author and the story, with evidence of storytelling skills that give hope for a point to the story.

- emphasize the point or arc (plot or emotional) of a scene.

- give a sense of meaning or purpose to the scene.

In addition, a chapter break can:

- affect pacing

- add a beat of story, plot, characterization, or emotion

- let emotion sink in

- create a mini or temporary cliffhanger

- add tension

All of those reasons can affect where a chapter break might feel like it’s “right” or “wrong.” So if our instinct isn’t helping, we can think about those effects chapter breaks might have on our story to pinpoint a good spot.

Whether we keep those benefits in mind while drafting and build our story with chapters, or we focus only on creating complete-feeling scenes and worry about the chapter breaks—and benefits—later, the better we understand our options, the better chance we have of finding the process that works best for us. *smile*

Do you understand the differences between chapters and scenes? Do you build a story up with chapters or scenes? Have you ever tried the other way? Does this post give you ideas of other options to try? Can you think of other ways chapter breaks affect our story?

Pin It

I tried going by chapters when I started, but now I just write scenes, with hooks at the ends of every one if I possibly can 🙂

When I’ve finished the second draft, I sort the scenes into chapters, generally putting the biggest hook at the end of a chapter and then working from there. Scenes are of wildly varying lengths, but I try to keep the chapters within a fairly even range.

For extra fun, I use a symbol that’s thematic for the book as a scene-break marker. For Restoration Day it was fleurs-de-lis; for The Wound of Words it’s snowflakes.