Story Immersion: How Can We Improve Our Readers’ Experience? — Guest: Jefferson Smith

Earlier this year, we shared what pulls us into a story. As I mentioned in that post, the sense that I’m not just reading words on a page but experiencing a story is why I read fiction.

That idea of feeling and seeing the story—or at least of the real world fading into the background—is called story immersion. While some readers don’t prioritize that aspect of stories (and that’s okay), for me, the words need to disappear from the page for a story to earn a “good” or “engaging” label, and I know I’m not alone.

However, like I mentioned in that post, the elements that encourage readers to immerse themselves in a story are often just what we think of as good craft. So beyond the vague instruction to “write well,” what can we do to increase the connection readers feel with our story?

Luckily, we have a story-immersion expert with us today. *grin* Jefferson Smith is an indie author known for his ImmerseOrDie challenge on his blog.

I wrote about ImmerseOrDie a couple of years ago in the context of how to make sure readers don’t close our book:

“Every day he chooses a self-published book to read while exercising on his treadmill. Each time a book forces him out of the story, that’s a strike. He gives each book three strikes—additional chances to not lose his attention again. At three strikes, the book is closed.

…I liked his approach because the number one piece of advice for story quality is:

Keep readers in the story.”

As I said above, story immersion is one of my favorite things about reading fiction, so I’m thrilled to have Jefferson here today, sharing his expertise. He has the inside scoop on specific things we can do (beyond simply avoiding common craft mistakes) that will make our stories more immersive.

Please welcome Jefferson Smith! *smile*

*****

Connecting The Dots:

How to Create Reader Immersion and then Kick It Up to Eleven

by Jefferson Smith

Hi. My name is Jefferson Smith and I’m here today to talk about immersive writing.

I’m a Canadian fantasy and science fiction writer, but that alone is no reason why anyone should listen to my theories. After all, I’m not some household name you can look to as a shining example of how to pattern your career. So why on earth should you give a damn what I have to say on the subject of engaging readers?

The short answer is: because I’ve made a fairly thorough and public study of the topic.

What Is Story Immersion? The Background…

For several years now, I’ve been running ImmerseOrDie: a web site dedicated to dissecting indie novels and analyzing what works—and what doesn’t—when it comes to creating and sustaining reader immersion. In the three years we’ve been doing it, we’ve examined over 600 books and cataloged nearly 2,000 specific examples of things that break the immersive spell.

The problem is that, with two or three new reports being posted every week, there are far too many of them for me to simply point at the archive and say, “Authors, go forth and self-educate.”

So, to supplement that self-help resource, I’ve been trying to distill the experience and summarize our findings into smaller, more bite-sized pieces for time-strapped writers like yourself to ingest.

- That’s why we created an index of the 50 most common mistakes that break immersion, complete with explanations and excerpts from real books that demonstrate the problem.

- It’s why we’ve started a YouTube channel in which we do 5-minute deep dives into some of the most interesting types of mistakes, examining why they break immersion and what you can do to avoid them.

- It’s also why I post handy immersion-preserving tips every day in my Twitter feed, each of which includes a link to a specific report that discusses the problem in more detail.

But even with all these outlets, I still haven’t found a way to encapsulate the fundamental recipe that underlies it all. And that’s what I’m going to try to do today.

How Do We Increase Story Immersion?

If you’ve seen the videos, you’ll know that I close every episode with: “Remember: Immersion happens naturally. All you have to do is get out of the way.” And I really do believe that’s true.

Immersion is a totally natural state for a reader to slip into. So the first and biggest hurdle to making your work immersive is to become aware of the kinds of mistakes that can disrupt immersion, and then stop making them.

That, however, is not enough.

Sure, We Don’t Want to Disrupt the Reader Experience…And?

It’s akin to a furniture craftsman learning to plane and sand his work before selling it. No customer wants to get their butts snagged on a sharp sliver of wood, just as no reader wants to have their mind’s eye yanked up out of the story world because of some clumsy writing or editing gaffe.

So it’s a necessary step, but it is not sufficient. It isn’t enough that readers be able to start your book and reach the end without throwing it against the wall in frustration.

We want more than that. We want them to reach the bottom of that final page with hearts pounding, lungs heaving, breathless with excitement, and wide-eyed with wonder at the rush of the experience you’ve just given them.

Reaching Story Immersion: Expert Level

So how do we do that? Emotional investment of that calibre doesn’t come from just simple immersion; it requires something even deeper than that. It comes from something I call “transception.”

Owing allegiance to concepts like reception, perception, and even transciever, transception is my term for the state a reader achieves when every sense they have has been disconnected from the situations, problems, and experiences of the physical world around them, and has instead been rewired into the situations, problems, and experiences of your created world.

You control the horizontal. You control the vertical. They are no longer thinking about your story; they are thinking within your story. Feeling it. Living it right alongside your characters.

How Can We Increase Story Immersion? Study Storytelling First

Regardless of genre, style, or voice, that is the ultimate goal I think most fiction writers are aiming for. And to achieve it, I think it’s helpful to look at why humans are drawn to stories in the first place.

Storytelling as Survival Tool

Language is one of the most powerful technologies ever invented. With it, humans first gained the ability to share information, and the most crucial piece of information we had to share was our experience. We could finally warn each other about the tiger hiding in the trees ahead, or about the dark cloud that flung a brilliant sky-spear down to turn Ogg into charcoal.

Language was so useful that it enabled us to recount important survival stories, and thereby learn from each other’s experience as well as our own, and live better, longer lives as a result. And any behavior that improves longevity tends to get encoded into the genetic hard-wiring of our collective instincts.

So our passion for stories can actually be seen as an ancient, life-and-death survival tool that we’ve co-opted for entertainment purposes. Much like we’ve done with food and sex.

Storytelling as Training Tool

On the surface, we now read stories for fun. But deep down inside, our animal hindbrain still sees them as a training tool.

By observing what’s happening in a story, it can make predictions about what is going to happen next, and then it compels us to read on to see if those predictions were correct.

You might be reading a tale about a guy walking down a dark alley and hearing a footstep in the shadows ahead, but when you instinctively think “It’s a mugger. Run!” that’s your real-life early warning system running a prediction test, hoping to learn something from this fiction that it can use later to avoid, or at least deal with, similar dangers in the real world.

And this, I think, is the gold-nugget observation that gives us insight into how immersion and transception work.

Storytelling Instincts Mean Our Brains Want to Learn

At the subconscious, cognitive level, readers are not looking for a series of events to be related to them as static, concluded actions.

They’re looking for a series of situations to unfold before them as they go, so they can make judgments about what those events mean and predictions about what’s going to happen next. Then they keep reading to discover whether their predictions were correct.

This is why showing is so much more important than telling:

- “Telling” is what we call it when we tell the reader what judgments to make.

- Conversely, “showing” is what we call it when we present her with the sensory evidence and let her draw her conclusions for herself.

When you tell a reader that Ken is an *sshole, you short-circuit her ability to see Ken behaving like an *sshole, make the judgment for herself, and then see that judgment proven true later. In other words, “telling” removes the entire reason she’s reading the story in the first place. That’s why we don’t like stories told that way.

How Does This Understanding Help Us Write Immersive Stories?

So the key to creating immersion then is to:

- keep laying down a trail of dots for the reader to pick up, and then…

- give her the time to connect them together, and…

- reach conclusions for herself about what they mean.

Think about how you experience your world on a day-to-day basis. You look around, you see things happening, you gather additional information from sound and touch and smell, and you draw conclusions.

You see a stove that’s glowing orange. You notice distortion ripples in the air above it. You conclude that it’s hot. That’s the two-way street of observation and inference that engages you with your life.

So we need to do the same thing with our writing. And when we succeed, readers are immersed into the fictional experience as deeply as they are into their real lives.

Now Add Stakes for Deeper Immersion

But how do we go that next level deeper? How do we go from mere sensory immersion to full-blown, emotionally arresting transception?

The key difference is one of stakes.

Want readers to immerse themselves in your story? Check out these tips... Click To TweetRemember how I started by equating stories with survival? Well, a routine situation can serve as a mundane test of that emergency-prediction system, but to really get the attention of that animal hind-brain, we need the situation to either be a new one, or to have an increased cost if we get it wrong.

Imagine a dinner table scene in which a boy’s father lectures him about his lack of responsibility. The reader can see the table, hear the clanking of cutlery and the awkward silences, maybe even see the worried glances between mother and sister. But that’s a simple sensory immersion.

It doesn’t grab the reader with the throat-grip of real transception, because in and of itself, the stakes of that scene are too low. There’s nothing particularly important going on, other than a commonplace friction between father and son.

Example of Adding Stakes to Increase Reader Connection

But what if I told you that the father is at his wit’s end and is considering kicking the boy out? And what if I piled even more onto the situation by telling you that the boy is secretly involved in a government operation to save the town, but that for it to succeed, everybody has to believe that he is exactly as lazy as his father believes?

Suddenly, that same dinner-table argument crackles with emotional tension. Not because I’ve changed even a single word of the original narration, but because now it means something.

If I lay my trail of breadcrumbs properly, the reader can see both situations. She understands what each of father and son has at stake and thereby is able to leap to much more gut-wrenching conclusions about what the continued friction is costing each of them.

So now, at the end of the scene, when the boy forces himself to shrug disinterestedly and walk away from his father in mid-rant, she’ll be devestated by the implications of that choice. How could she not be? These implications matter.

And that’s what transception is all about.

Final Thoughts

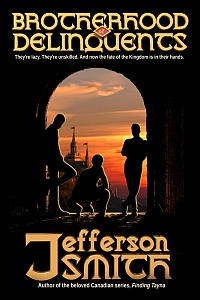

That scene isn’t just a toy example I created for this article; it’s actually a pivotal scene in Brotherhood Of Delinquents. I wrote it when I was first starting to formalize this theory of transception, and it remains to this day one of my favorite scenes.

But that’s just me. To you, this is all just bluster and bile if it doesn’t help you with your scenes. So take it for a spin and see if it does.

The next time you’re writing a scene and you want it to have greater emotional heft, try a less-is-more approach. Don’t tell readers how important everything is. Instead, let them see how important each character’s goals are, and then put them into a scene where it becomes clear that they aren’t going to get what they want.

If you provide the context, and show them high enough stakes, the readers will provide far more emotion than you can ever describe. Because they’re not being told what to feel. They’re feeling it spontaneously for themselves.

Or, putting it in a more familiar form: transception happens naturally. All you have to do is provide the context, raise the stakes, and then get out of the way.

*****

Jefferson Smith is a liar of the first order. He has lied to kings and queens; he has lied to hobos and urchins. He has lied to the mightiest of the mighty and to the lowest of the low. He is probably lying to you now.

Jefferson Smith is a liar of the first order. He has lied to kings and queens; he has lied to hobos and urchins. He has lied to the mightiest of the mighty and to the lowest of the low. He is probably lying to you now.

But in every lie there is a grain of truth, and in every telling a bewitchment. So it should come as no surprise that Jefferson bends his talents to the one craft that reveres both the liar and the lie, weaving entire worlds out of falsity and invention, raveled up in strands of guile.

He is an author, and you will not find his equal in any other sphere. Or so he keeps telling us.

Web | Twitter | Google+ | Facebook

*****

About Brotherhood of Delinquents

They’re lazy. They’re unskilled. And now the fate of the Kingdom is in their hands.

They’re lazy. They’re unskilled. And now the fate of the Kingdom is in their hands.

Tam, Kern, and Merrik are all failing at life: a homeless thief, a disgraced baker’s apprentice, and an incompetent smith. But witnessing a strange ritual in the middle of the night sets them on a collision course with destiny—and with each other.

Accused of crimes they did not commit, the boys must band together to clear their names. And in the process, they just might have to do something useful, like battle monsters and save the city. But frankly, that sounds a lot like work.

Kindle | Kobo | Nook | Apple | Print

*****

Thank you, Jefferson! Those are great insights into telling versus showing as well as what many look for in stories. While not every reader thirsts for story immersion the way you and I do, we can all learn from your points here about the importance of including stakes—and consequences—that matter.

Jefferson touches on several ideas that I’ve covered in my blog and shows why those craft skills are necessary for our writing. On some level, good storytelling is about including the right context for readers to understand why the story situations and stakes matter.

As Jefferson said, if readers feel like part of the story and understand the subtext of events, obstacles, and interactions, the flow of the story will carry them along. All we have to do is set everything up and then get out of the way, as readers will do the work to live in the story. *smile*

Have you noticed differences in the depth of your immersion when reading stories? Do you agree with Jefferson’s description of standard “showing”-style immersion versus the emotionally invested style of transception? Or do you have a different take of the various immersion levels and what creates them? Did this post trigger any other insights for you? Do you have any questions for Jefferson?

Pin It

[…] author do to create and then enhance the immersive experience? Well, I explore that today in a guest post over on Jami Gold’s site. It’s a deep dive on the nature of immersion, and it […]

I liked the insight that the reader makes predictions and then keeps reading to see if they pan out. It’s what I do.

What a great explanation. Thank you.

Thanks. Poor spelling, punctuation, grammar throws me out of the story and onto the written page every time.

Hey, I love the explanation of telling stories for survival, and that we predict what will happen in the story and get worried for the characters. I love romances, in particular. It’s kind of an emotional survival for the protagonists, since they want to find a lifelong companion, partner, and best friend. What will the boys do (in a gay romance) when they see each other for the first time? What will happen after they have had their first interactions, and have made interesting impressions on each other? If they become lovers, what happens next? What difficulties will they face as a couple? (This could include societal obstacles like homophobia, which is definitely related to both physical and psychological survival.) As for the telling “Gary was an *sshole,” I would say that telling can be helpful sometimes. For instance, the third or first person narrator could tell you, “Gary was a narcissistic jerk.” But later you read the story and discover that Gary has actually done some impressively altruistic things, and you learn that the narrator had a limited and skewed perception of the truth. The narrator didn’t know Gary as a whole, complex person. And so the reader learns not to trust the narrator too much, lol. Hmm strangely enough, I was more interested in becoming immersed in books when I was younger. But nowadays, I don’t care as much, especially because I get so wrapped up in listening to the rhythm and sounds of the words, sentences, and… — Read More »

[…] reader to get so caught up in the story that the real world disappears. Jefferson Smith discusses story immersion, Donald Maass states that suspending disbelief starts with a story world that feels real, and […]

[…] make appropriate choices to increase reader immersion […]

[…] make appropriate choices to increase reader immersion […]

[…] Story Immersion: How Can We Improve Our Readers’ Experience? — Guest: Jefferson Smith The Secret of Scenes that Keep your Readers Reading How to Hook Readers and Reel Them into Your Scenes 3 tips to keep your reader reading Story Immersion: What Pulls You In? […]

[…] Tattoo” introduces a complex web of codes and secrets that lie at the heart of the mystery, immersing readers in a gripping tale of intrigue and […]