Sentence Flow: Fixing Choppy Writing

Whenever I think I’m nearly done with my writing and read through my work for the umpteenth time, I always experience a moment (or whole days) where I think my writing sounds too choppy. After years of experience with this phenomenon, I think I’ve figured out that it’s just a function of how my brain works when reading text I’m already extremely familiar with. At least, I hope that’s all it is. *smile*

However, sometimes our writing really is choppy. In that case, we need to reword to create a better flow for our sentences.

What is choppy writing, what causes it, and how can we fix it? Let’s take a look…

What Is Choppy Writing?

Choppy writing is what we call it when our sentences lack flow. There’s no rhythm or transitions carrying readers from one sentence to the next.

What causes choppy writing and how can we fix it? Click To TweetFrom a reader’s point of view, choppy writing can make every event in our story “sound” to the mind’s ear like it’s being delivered in a voiceless monotone. This can result in a poor sense of pacing or tension from our writing.

Choppy writing can also make our sentences feel disjointed, like they’ve been assembled randomly. Readers can lose focus on our story because they’re not drawn in and immersed in our writing to the point that they forget they’re reading words on a page or screen.

In short, our story deserves better than feeling like it could belong in an early reader for kids. *grin* But how do we find and fix writing that doesn’t flow?

4 Causes of Choppy Writing

As I alluded to above, choppiness can be caused by a couple of different issues, and each cause will have a different solution. So let’s dig deeper into four of the most common causes of choppy writing.

Cause #1: Lack of Transitions

Look at the paragraph above. You see that “as I alluded to above” phrase at the beginning of the paragraph? That’s one example of how we might transition from one thought to the next when writing non-fiction.

What are 4 common causes (and solutions) of choppy writing? Click To TweetIn non-fiction, it’s often obvious when we move from one point to another, so adding transitions might come more naturally to us when we write in that world. In addition to introductory phrases, we might also use headings, bullet points, or other techniques to introduce shifts.

However, fiction writing shifts from one idea to the next as well, so transitions are needed in that world too. Again, we can use introductory phrases (even short ones like “Besides…” can help), as well as referencing a noun or action in a previous sentence or just simply following the flow of cause and effect.

For example, if our character is thinking about how much they’re against doing something and the next sentence has them doing it without any explanation of their changed action or decision, readers can feel like they missed part of the character’s journey. A sigh or grumble to the inevitability, an internal pep talk about its necessity, or a sudden new urgency can all signal the change as our character gathers the motivation to get the thing done.

Cause #2: Lack of Order

Sometimes when we draft, our sentences might bounce from one topic to another and then back. That back and forth can distract readers and make it harder for them to process what we’re trying to share.

One way to think of our storytelling is to consider our narrative like a tour guide. Imagine being on a tour where the guide pointed out a statue to our left, then pointed out a painting on our right, and then proceeded to tell us a story of the history of the statue back on our left.

That’d feel pretty disjointed, right? Our storytelling can do the same thing if the focus of our sentences creates a back-and-forth feeling.

Here’s an example from the first page of my story Pure Sacrifice, before and after editing:

Before:

Heat crept up her cheeks. She dropped her gaze to the sketchpad and let her light hair slide forward. He hadn’t turned his head in her direction, hadn’t so much as twitched. Her face burned regardless, as though behind his shades, he’d focused on her. Impossible.

No one ever noticed her.

Notice how the focus shifts from the heat in her cheeks to her gaze and hair and then back to her face burning? That can make our writing feel distracted and not as strong, as one idea is literally interrupting another.

In editing, I could have tried moving sentences or ideas around to avoid that bouncing focus. In this case, though, the original was wordy, so I just removed the interrupting line and used “regardless” as a transition to connect the sentences.

After:

Heat crept up her cheeks. Not that he’d turned in her direction, or even twitched. Regardless, her face burned as though behind his shades, he’d focused on her.

Impossible. No one ever noticed her.

In other words, we might want to group similar ideas together in a paragraph. Sentences about our character’s senses of their surroundings could go together, and sentences about their decision process could go together, and so on.

At the same time, we also want to watch out for too much repetition of the same type of information in a row. For example, after a couple of paragraphs focusing on action, such as a fistfight, we probably want to mix in at least a sentence of dialogue or of how the character is thinking, feeling, or reacting to all the action, just to add variety.

Cause #3: Lack of Rhythm

I’ve talked before about how our writing can have rhythm:

“Rhythmic writing will often sound like waves of stressed and unstressed syllables and sentences. More importantly for good writing, the cadence of the sentences pushes readers forward, just like how we talk about a song’s “driving beat,” and those stressed syllables or sentences will fall on those words or ideas we want to emphasize.” …

Rhythm creates and connects to emotions.

Even as we shift ideas from one sentence or paragraph to the next, rhythm helps carry readers forward, creating a sense of connection between our ideas and our story. In turn, that forward movement keeps up our story’s pace and reader interest.

But how do we create rhythm? As I mention in the post linked above, the aspects of our writing that affect its rhythm include:

- sentence length (including fragments)

- power words (especially at sentence endings)

- punctuation, paragraphing, etc.

- rhetorical devices, such as anaphora

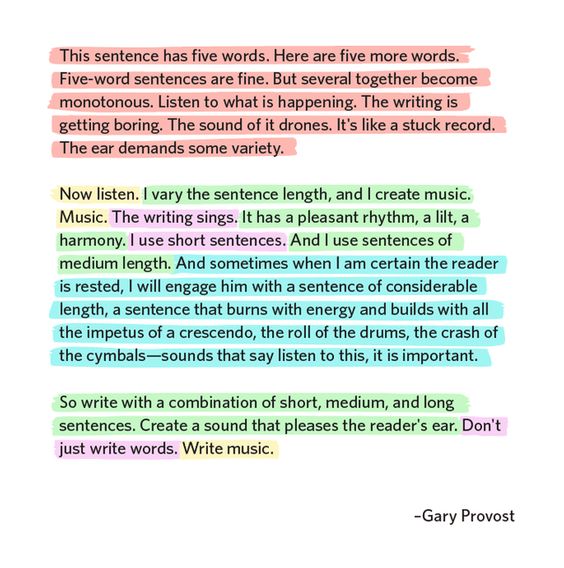

This famous example by Gary Provost uses all of those bulleted aspects to illustrate how rhythm affects our sentences’ flow:

Take the time to read that example aloud, Or even if we just say the words “aloud” in our mind’s ear, we’ll notice the difference that rhythm makes.

Cause #4: Lack of Sentence Variety

Those first two causes above might have been a surprise, as transitions and sentence order aren’t necessarily the usual culprits when we think of choppy writing. And while rhythm is great, it isn’t always necessary (or possible), as some sentences are just going to be basic no matter what we do.

However, choppiness isn’t just about any individual sentence. Choppiness is caused by how the sentences play together, how one sentence flows into the next and/or sounds compared to its neighbors.

Beyond sentence length, there’s a reason why Gary Provost’s first paragraph is monotonous. Not only do those sentences each have five words, but most of them also share the same simple sentence structure:

- subject (like a noun phrase)

- linking verb (not even action verbs)

- subject complement (linking verbs have subject complements like how action verbs have objects)

Subject-verb-object sentences are the workhorses of our writing, but variety helps break up choppiness and improve our rhythm. So we want to mix and match all four types of sentence structures:

- Simple Sentence: single subject/verb independent clause

She rolled her eyes. - Compound Sentence: two or more independent clauses joined by a conjunction (one of the FANBOYS: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) or a semicolon

She rolled her eyes, but her mother ignored her. - Complex Sentence: single independent clause connected to a dependent clause with a subordinating conjunction (before, when, if, who, etc.)

When she rolled her eyes, her mother ignored her. - Compound-Complex Sentence: two or more independent clauses and one or more dependent clauses

When she rolled her eyes, her mother ignored her, so she stomped her foot to force her mother’s attention.

Let’s go back to Gary Provost’s example. Even if we stick to most of the “boring” words in that first paragraph of his, we can break up the monotonous and choppy feel by mixing up sentence structures:

This sentence has five words, and here are five more. Five-word sentences are fine, but several together become monotonous. If we listen to what is happening, we notice the writing is getting boring. The sound of it drones like a stuck record because the ear demands some variety.

Obviously that’s still not super interesting, but two compound sentences followed by two complex sentences are more interesting than eight simple sentences in a row. That said, we’d probably want to throw in a simple sentence soon, just to mix things up because variety is good. *smile*

How Can We Tell If Our Writing Is Choppy?

Great! So we now know four things to look at when our writing is choppy. But how do we know if our work suffers from that problem?

As I mentioned up above, sometimes when I’m sick of editing and reading my story at the end of the process, my writing feels choppy to me even though it’s not. So how can we tell for sure?

First, we can listen to feedback from our beta readers, critique partners, or editors. But especially if we want to fix problems during a self-editing session before we share our work, the best way we can discover the true nature of our writing is by reading it aloud. (Or if we have a willing partner, we could listen while someone else reads it aloud to us.)

Reading our story aloud allows us to feel the flow of our sentences. We can hear the variety we use, whether we’re talking about sentence lengths or structures or use of transitional phrases or whatever. (And again, variety is good.) As a bonus, the read-aloud technique is also what mostly reassures me when I think my almost-done story is crap, so for that alone, I’m grateful for what the process can reveal. *grin*

10 Year Blogiversary Reminder!

My blogiversary is coming up mid-July, and that means 2 things:

As I announced last week, after 1000+ posts and ten years of publishing articles every Tuesday and Thursday, I’m giving myself the gift of an irregular schedule. So this is a great time to make sure you’re signed up for my blog-post newsletter so you don’t miss any of my new scheduled-when-I-feel-like-it posts! 😉

My blogiversary also means that it’s time to enter my 10th Annual Blogiversary Contest! The more comments we get on that post, the more winners we’ll have. 😀

Have you ever noticed that your writing feels choppy? Or have others mentioned that your sentences don’t flow? What have you tried to fix the problem? Does this post give you more ideas? Do you have any insights to add about the causes or solutions of choppy writing?

Pin It

Jami, this is solid advice. And as you say, the “cure” is to read your work out loud. Not only does that make the rhythm (or lack) more noticeable, but lets you visualize the action and metaphors more distinctly.

Thank you for this much-needed discussion. I need a workbook with exercises to help me eliminate choppy writing. That’s what I was searching for most of yesterday. If you know of anything, please let me know. Choppy sentences and potholes are my current downfalls in writing fiction. I am slowly conquering my propensity to tell rather than show.

Hi Stephanie,

Hmm, I don’t know of a workbook, but that’s a good point. I’ll keep my eye open for one. 🙂 Thanks for stopping by!

It just so happens that I am having trouble with choppy writing in a particular chapter. I’ve been blaming it on my mood. This article helps a lot. I believe my problem is mostly with transitions and lack of sentence variety. I’m also not so good at metaphors and similes. Now I think I’m ready to go back and review that chapter. Thanks! :0)

[…] a professional editor. Henry McLaughlin dives into the art of self-editing, Jamie Gold discusses fixing sentence flow and choppy writing, and James Scott Bell looks at how to move from one scene to the […]