Character Descriptions: Avoiding the Boring Stuff — Guest: Angela Ackerman

I’m offline this week, but I have two phenomenal guest posters lined up for all of us. First, we have superstar Angela Ackerman here to talk about character descriptions today. Yay!

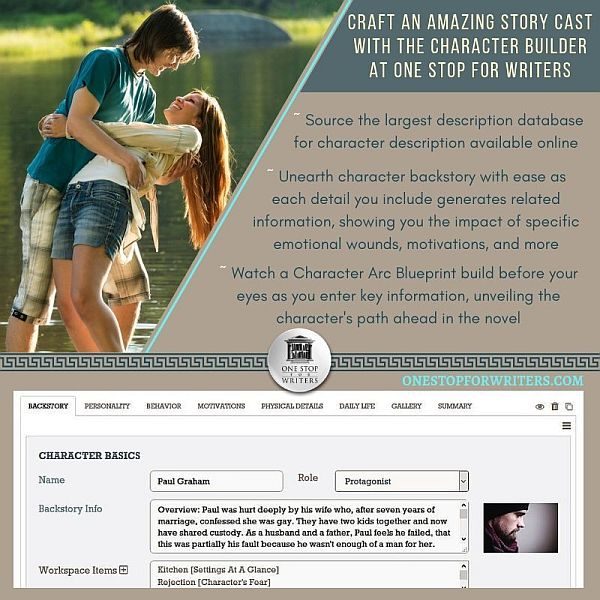

Whether we let our muse guide us, use character sheets, search for inspiration images, or explore the Character Builder resource available on Angela and Becca Puglisi’s One Stop for Writers site, we usually need to think about the physical appearance of our characters at some point during our writing process. But description can be tricky to write, as it’s too often flat and boring to readers.

Luckily, Angela—who, along with Becca, wrote the Emotion Thesaurus book (and other Thesaurus books) and the Writers Helping Writers site—is a character expert. She’s sharing seven methods we can use to keep our character descriptions from slowing down our story.

Please welcome Angela Ackerman! *smile*

*****

7 Ways to Describe a Character’s Physical Appearance

By Angela Ackerman

We all know characters are the beating heart of a story. Fashioned from imagination clay and given life by an author, these fictional people have yearnings, dreams, and fears just like us. They also have a past—one filled with challenges, strife, and hope—and this collection of experiences shape them into the person readers meet on the doorstep of chapter one.

Digging deep to explore a character’s hidden truths is hard and necessary work. I spend a lot of time coaching writers to drill down into the essence of who their character is so that when they write their behavior, every action and choice is driven by their motivation and authentic to them.

But there’s another aspect of character description that is easy to forget about or gloss over: their physical appearance.

How Much Physical Description Do We Need?

Readers need to build an image of the character in their minds to fully connect to them. This type of description requires balance though, because without it, a writer will end up in one of two camps:

- going all-in and conveying every hair follicle, scar, and curve, or

- backing away to provide a sketchy outline that forces readers to fill in the blanks.

Both have pros and cons.

How much character description should we include? @AngelaAckerman shares her insights Click To TweetCopious description paints an accurate picture for readers…if they bother to read it. More likely they’ll start skimming (and miss your beautiful details) because it’s killing the forward momentum of the story.

Likewise, a too-basic outline will involve readers, but making them work hard to imagine the character means it takes longer for them to form a bond. With short attention spans, that’s risky business.

Ideally, we want to meet in the middle of these extremes.

How Should We Share Description Information?

Of course, this leads to another problem…knowing how to relay the most important details in an active, engaging way.

There’s always a temptation to rush the brush strokes at the beginning so we can “get on with the story,” but we must resist this urge as it can lead to list-like description, look-in-the-mirror clichés, or the character describing themselves in a way that is unnatural, causing breaks in POV.

So, what’s the best delivery? It’s twofold: slipping detail in as part of the action and making it meaningful.

In this way, a detail becomes an interesting puzzle piece that the reader will want to collect. Readers love following a trail of clues, so layering details that help them understand the context of the situation better will not only provide them with an image, it can also help them understand who the character is deep down and further the story.

7 Ways to Make Description Active and Meaningful

Here are 7 ways to slip in description for appearance and physicality.

#1: Clothing Choice

What your character wears can convey so much more than style and a favorite color. Clothing is the armor they wear to face the day.

How can we make character description active and meaningful? @AngelaAckerman shares 7 techniques Click To TweetThink about why they choose to wear what they do: are they trying to fit in and be accepted, or stand out? Is it functional for the mission in this scene, or will it be a hinderance?

Clothing choice can allude to personality, values, and motives. Readers may infer a character wearing a plain navy skirt and matching cardigan buttoned to the top is someone who is prim, respectful, and lives life on the sidelines by supporting others.

Would readers conclude the same about a woman who chooses fashionably shredded red jeans that match her lipstick and sneakers? Likely not.

#2: Personal Items

You probably won’t go anywhere without your phone, purse, wallet or favorite jacket, so what about your character?

Do they have items that act like a neon sign to readers as to who they are, perhaps like a leather jacket and a motorcycle helmet they carry with them wherever they go? Is their locker at work crammed with workout gear, protein powder, and smells like a hot yoga studio?

Think about the items they use daily, what they have on hand, and even the jewelry or adornments they wear. These all help to create that image for readers while revealing something more, like interests, priorities, lifestyle choices, or even neuroses and health conditions.

#3: Observations of Others

Rarely is a character alone in a story, so use other characters as a vehicle to get details across.

“Blue, again?” Lori shook her head. “You said you were done, that you were tired of your hair sabotaging your interviews.”

This simple statement immediately shows us that the character in question has blue hair, but it does more than that…it reveals they see-saw between conformity and individuality, and even though they need a job, their rebellious streak is winning. Wow, all that from a single hit of dialogue!

Just make sure if you use this technique it doesn’t become on-the-nose dialogue, or all the power of characterizing detail is lost.

4: Making Comparisons

We all have issues of self-worth to some degree, so naturally our characters will too, meaning they compare themselves to others. Having your character admire another’s clothing, presence, movement, status, age…all these things can help us see how your character doesn’t quite align with the person they’re observing.

Leo lifted an entire stack of two-by-sixes like it was nothing and carried it across the yard. Great. I grabbed a second board, so I didn’t look quite so bad.

In this scene, two men are working on a home construction project, but clearly Leo is younger, more fit, or both. A few extra details could provide more clues, like strain in the character’s shoulders at the extra burden, a memory surfacing about how he used to haul loads like that no problem two decades earlier, or even a hen-pecking wife rushing out to scold him for carting around far more than he should carry. In any case, this comparison shows our character has his mental measuring stick out and he’s pushing himself to take on more as a result.

And did you notice we are providing clues about the character’s physicality by showing what isn’t there? Indirect description can lead to fresh writing, so don’t be afraid to experiment!

#5: Awareness of Persona

Your character functions in a world rife with the expectations of others, just as we experience in real life. Navigating safely sometimes means conforming or masking vulnerabilities, so your character will project an image of what they want others to see: a persona.

They may dress, behave, and speak a certain way, but their thoughts will always be their own. If you show your character’s deliberate choices to fit in and why, you can self-describe in a way that feels natural. Readers will be able to picture the character’s appearance, and even better, see beneath the persona to their true self and their motivation for using camouflage in the first place.

Take this example:

Mary chose the yellow flats Mother had bought for her birthday and squeezed into them. They pinched and rubbed with the promise of blisters to come. Was the too-small size deliberate? She laughed. Of course it was. The pain didn’t matter though, because her mother would notice how the shoes matched her sundress and approve. Today was all about controlling the situation, and that meant doing everything possible to prevent her mother’s spiky moods from ruining everything. Again.

#6: Self-Deprecation and Jokes

Another realistic avenue for describing an appearance is to show a window into a character’s thoughts when they believe they don’t measure up or how they respond with self-deprecating dialogue when another character attempts a kind word.

For example:

“Dress codes, good grief. Clearly no one follows them except me. When I hit the stage, people are going to think they’re attending a funeral service”

This description gives us a visual, and we can imagine the character standing there fidgeting in his dark suit, feeling like a fish out of water, nervous on the cusp of his speech or whatever is about to put him into the spotlight. Whenever possible, challenge yourself to make sure your description is adding to the story and enhancing the emotions in the scene.

#7: Movement

How your character moves, what they touch or avoid, and how they interact with the setting will help readers see your character clearly. Movement adds fluidity and often it’s the perfect place to slip in description because it works with the pace instead of against it.

Consider this example:

Laura’s stride paused and her back stiffened. I sucked in a breath. Despite the loud music, she’d obviously caught Jonas’ careless words. Even turned away, I could imagine my sister’s features tightening before she regained control and smoothed her emotions into glass. A beat later, she was moving again, but this time when her black heels clacked the tile, they felt like exclamation marks, each one a promise that Jonas would soon regret his words.

Here we paint an image using both what can and cannot be seen. It feels authentic because the sisterly relationship implies an authority to interpret the other’s responses and read into their meaning. In this case details are sketched (a straight back, controlled posture, high heels), and they are used to build hit after hit of emotion, amping up the tension. Jonas, whoever he is, better watch his back.

Add Description with Purpose

Whatever method you choose to describe your character’s appearance, remember to share details that matter. Description is powered up when it does double or triple duty by characterizing, revealing emotion, hinting at motives or desires, and pushing the story forward, not just painting that picture for readers.

For even more advice on this topic, check out Jami’s post here.

*****

Angela Ackerman is a writing coach, international speaker, and co-author of the bestselling book, The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Expression (now a expanded 2nd edition) as well as six others. Her books are available in seven languages, are sourced by US universities, and are used by novelists, screenwriters, editors, and psychologists around the world.

Angela Ackerman is a writing coach, international speaker, and co-author of the bestselling book, The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Expression (now a expanded 2nd edition) as well as six others. Her books are available in seven languages, are sourced by US universities, and are used by novelists, screenwriters, editors, and psychologists around the world.

Angela is also the co-founder of the popular site Writers Helping Writers, as well as One Stop for Writers, an innovative online library built to help writers elevate their storytelling.

Website | Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

*****

Need help organizing your characters’ information? Try the Character Builder!

One Stop for Writers’ Character Builder is a hyper-intelligent characterization tool that will help you plan unique, deep characters in a fraction of the time. Once you create a custom profile for each character, compare them! You’ll be able to view their histories, personality traits, emotional wounds, goals and more, helping you to spot places where points of natural friction exist.

*****

Thank you, Angela! I love how your tips run the gamut—from descriptions that we typically think of as boring (such as clothing) to descriptions we might not think of as related to physical appearance at all (such as movement)—and yet you show how it all can help our story and not drag down the pace.

Angela and I both love subtext, and these techniques are a great example of how we can share something with our readers without coming out and saying it directly. Yet as we try to find the right balance of character description for our story, we should also keep in mind that there’s no “one right answer.”

The “right” amount of character description greatly depends on our genre (and subgenre), our voice, our story’s tone and style, etc. For example, my genre of romance typically uses more character description than other genres. Similarly, chatty and/or observant characters will likely point out more details about characters than other points of view.

No matter our story or balance of description, these seven techniques from Angela will make our character descriptions more active and meaningful. In turn, those strong descriptions can prevent readers from being bored or skipping over our prose and, at the same time, help readers connect more with our characters. *smile*

Have you seen examples of “bad” or boring character descriptions? Do you remember any good examples (or if they’re good, do they not register with you)? Do you struggle with writing character descriptions? What’s your favorite method of describing a character’s appearance? Do you have any questions for Angela?

Pin It

Thanks so much for having me here Jami! I hope you are having a fantastic trip!

I always remember reading a book, and in the very last chapter, the author noted that the MC was white. Throughout the entire book, I was visualizing the character as Morgan Freeman. Other than references to his age, there was no other real descriptions of the guy. So why did the author decide to tell me he was white at all? I thoroughly enjoyed the book anyway! And as a reader in general, I immediately skim over descriptions. I don’t need to be told what a character looks like – especially when what the author thinks is attractive is a total turn-off for me (“Why would A be at all attracted to B? She must be an airhead…”). Descriptions don’t always work the way you think they will.

So when I write, I will leave “clues” rather than actual descriptions, things that explain why something happens the way it does (the outcome of a fight), or hints at what’s coming (dressed a little ruggedly just to meet a guy). And then I let the readers use their own experiences to decide what they look like. JMO, but if you’re writing the character well, the physical description isn’t really needed. Everything else will keep the reader going.

That is so weird, to wait until the end to describe someone as white. Like you I don’t always need a lot of description to go on as a reader, but I find it really frustrating when an author waits to pass on a highly specific detail until long after I’ve already got an image on my mind. So if it’s a detail like pink hair or the person is in a wheelchair or something along those lines, writers shouldn’t wait.

I also think that readers have different expectations when it comes to genre. Some, like historical, will go in greater depth than something more contemporary and if the author didn’t, readers would be upset. My point is more to think about how all description can do double duty, so no matter how much or how little a person uses, to try and include details that show emotion or characterization or subtext.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

Angela

Yeah, it was a real ‘slap in the face’ moment, that’s for sure. And it was a well-known author to boot.

I’m totally with you on using description as a sort of ‘adjective’ to other parts of the story. I agree with you also on the genre thing. Also location – you definitely want to put the reader in the right country.

Yikes. You’d think she would know better.

Great suggestions, Angela!

I would like to add that people tend to lead with different sensory modalities when processing information. Some people mainly process information visually, others are mainly auditory, and a smaller group are mainly kinesthetic (movement and visceral sensations).

About 65% of the U.S. population leads with the visual modality, so they need some description of a character early on, to help them form a mental picture. My guess is that the folks who say they don’t need any description are auditory processors. They don’t feel a need to visualize the character. They relate to the character through the dialog and descriptions of their actions.

As writers, we need to remember that not all readers process info the same way we do, so we need to provide enough physical description, plus the revealing dialog for the auditory folks, and the deep POV visceral sensations for the kinesthetics.

Yes, great point, Kassandra. I think providing a balance is the most layered approach not only to hit the spread, but also because it creates a deeper, richer connection to the character. We have a tenancy to over rely on visuals, and so choosing a few different ways to show our characters to readers will be more memorable in the long run. 🙂

[…] Angela here, who has been traveling the internet a bit lately. If you need help with making your Character’s Physical Description Stronger, I’ve got you covered. And if you’re focused on growing your audience, find out my 5 […]