An Authors’ Guide to Creative Commons — Guest: Deborah Makarios

With NaNoWriMo wrapping up, many writers will be looking forward to the next step of their publishing journey. Of course we need to edit and revise our work first, but what then?

For many writers, the focus has always been on deciding between the traditional publishing path, with querying and submitting, and the self-publishing path, putting our work up for sale on our own. However, there’s another aspect to publishing that we might not have thought of before: What rights we want over our work?

We’ve heard about copyright, sure, but there’s more to our rights than just claiming ownership. Those other rights are where Creative Commons (CC) comes into the picture.

Like many authors, I didn’t know much (anything) about Creative Commons licensing and figured it wouldn’t apply to our books. So when Deborah Makarios mentioned in the comments here a couple of months ago that she uses CC licensing for her stories, I invited her to share her insights into what Creative Commons is and how it might apply to authors.

Please welcome Deborah Makarios! *smile*

*****

An Introduction to Creative Commons

by Deborah Makarios

Hello, everybody! I’m delighted to be here at Jami’s invitation to talk a bit about Creative Commons: what it is, what it isn’t, and what that all means.

What Creative Commons Isn’t

Myth #1: Creative Commons Means Zero Rights

The biggest myth about Creative Commons licenses — and unfortunately it’s a prevalent one — is that anything under a CC license is free for anyone to do whatever they want with, including claiming it as their own work.

What do those Creative Commons notes with some text or images mean? Click To TweetThis is not true. It’s not even close to being true.

The loosest Creative Commons license is CC0, which is the same as releasing your work into the public domain. Pride and Prejudice is in the public domain. Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is in the public domain. Publish either of them under your own name, and you’ll be committing plagiarism, which is a kind of fraud, which is a crime (not to mention a sin in various major world religions).

What Austen’s works being in the public domain means, of course, is that you can use the phrase “it is a truth universally acknowledged” without the Austen family coming after you, baying for your blood — or rather, for your bank balance. Likewise with Beethoven — you can use dah-dah-dah-dum in all sorts of things without breaking the law, or having to hunt down whoever Beethoven or his descendants sold the rights to. (Or deal with their lawyers.)

Myth #2: Creative Commons Replaces Copyright

Another prevalent myth about Creative Commons is that it destroys (or replaces) copyright. This is also not true. Creative Commons is an add-on to copyright, not a replacement for it.

- A copyright notice basically tells the world “I have the rights to this work.”

- Following it with All Rights Reserved is like adding “and I’m keeping them.”

- A CC license says “and I’m sharing these ones but keeping this one” or something like that.

All Rights Reserved is such a standard in our culture that people assume it’s an automatic follow-on to © Author’s Name. But there are times when it’s just plain ridiculous.

Are you a knitter, or a crocheter, a quilter, or embroiderer? Have you ever photocopied a pattern out of a book for easier use, transport, or markup — or copied it by hand?

If the book was under the standard “all rights reserved” then I’m afraid you have launched yourself on a life of crime — even if the book was your own copy that you had bought and paid for.

In fact, some “all rights reserved” notices could even be interpreted to mean that it’s illegal to make any of the projects in the book — because that’s reproducing the content, which is forbidden in any form! Of course, you’re not likely to be had up in court for it (you can bring out your contraband crochet now) but it’s still not healthy for a culture to have normal activities be technically illegal.

The Creative Commons Licenses

So let’s have a look at what the Creative Commons licenses do — and don’t do. There are seven CC licenses, each of which has a different set of rights reserved or shared.

CC0 License

CC0 you’ve already met: that’s the public domain license. “Help yourself but remember fraud is still illegal.”

The public domain is what made Pride & Prejudice & Zombies possible. Images on Pixabay are also under this license, which is why I’ve used them to illustrate this post. You can freely use them on your blog (or book cover!) without breaking the law — as long as you don’t claim them as your own work.

CC-BY License

CC-BY means “help yourself as long as you attribute the original creator.”

So, for example, if Jane Smith publishes a book with a CC-BY license, John Brown can make it into a movie without any further permission or contracts or lawyers, as long as he says ‘based on The Book by Jane Smith’. This is good for Jane Smith, because anyone who sees the movie and likes it will then be interested in buying her book — and maybe any other books she’s written.

(My apologies for the boring English names — I didn’t want to disappear down the twin rabbit warrens of Finding Interesting Names and Googling Interesting Names To Make Sure There Isn’t A Real Person With That Name.)

CC-BY-SA License

Then there’s the CC-BY-SA license. The SA stands for Share Alike, and this means that if people use your work, they have to share what they’ve made from your work the same way.

Can authors use Creative Commons licenses? Is it a good idea or not? Click To TweetTo continue with the Smith/Brown example, if Jane Smith used this license, John Brown wouldn’t be able to put an All Rights Reserved license on his film — he’d have to let other people use the film the way he used Jane’s book. Share and share alike.

To give you another example, consider this very blog post that you are reading. Jami’s work (the introduction and, er, outroduction) are under an All Rights Reserved license. If you want to reuse or reproduce any of her content in any way, you need her permission.

The part of this post that I’ve contributed, however, is under a CC-BY-SA license. So if you’re going to reuse or reproduce my part of the content, you need to say who it’s by, i.e. me; and if you use this content in another work — a five act opera about copyright, say (how do I know how you spend your free time?) — then you need to share that work in the same way I’m sharing mine.

CC-BY-NC License

Slightly more restrictive than that is the CC-BY-NC license. NC stands for Non-Commercial, meaning you can use this work — again, as long as you say where you got it — but you can’t make money from what you make.

So if someone wanted to paint a picture of their favourite scene from Jane Smith’s book, they could do that, but they couldn’t paint it to sell, only for themselves or as a gift for a friend.

CC-BY-NC-SA License

There’s a version of this license with Share Alike on it too — the CC-BY-NC-SA license. Same deal, but you’ve got to Share Alike.

So if you gave that picture you painted to a friend, you can’t stop her putting it on her Christmas cards — always providing that she isn’t selling them.

CC-BY-ND License

Even more restrictive is the CC-BY-ND license, in which the ND stands for No Derivatives, meaning no works based on this work.

That means you can, for example, make copies of Jane’s ebook to sell on your website, but you can’t paint a painting of it, or adapt it into a play. You can’t make any changes or transformations, you can only share the work the way it is.

CC-BY-NC-ND

The most restrictive of all the licenses is the CC-BY-NC-ND license, which means you can’t make any derivative works, and you can’t use it for anything commercial.

So you could give your friend a copy of the ebook, but you can’t sell one. This is the license that the author Emma Darwin (yes, they’re related) uses for her writing blog, “This Itch of Writing”, and British soprano Charlotte Hoather uses for her blog.

Using Creative Commons Licenses

Of course, Jane Smith’s book is just an example here. Creative Commons licenses can be put on all sorts of things — books, music, films, photos, knitting patterns — anything that can be copyrighted, really. Because Creative Commons licenses don’t replace copyright, they work alongside it.

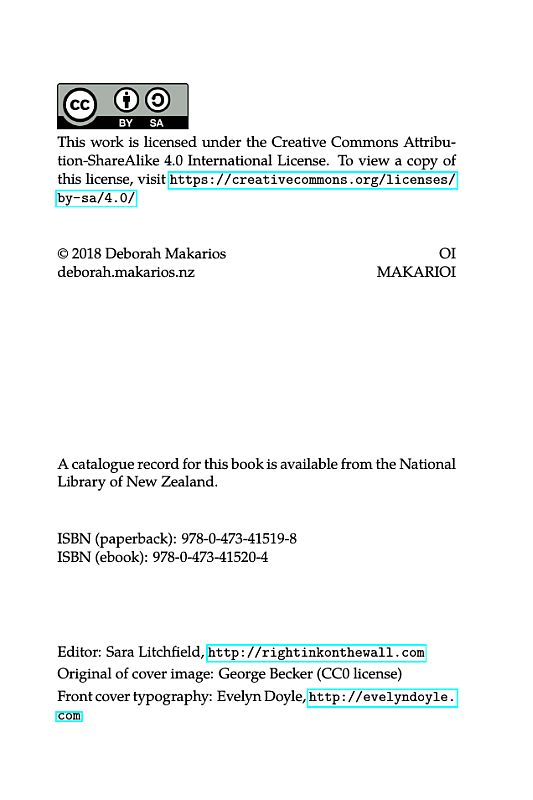

Let’s take my debut novel Restoration Day as an example. It’s under a CC-BY-SA license — Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike. I still own the copyright, so the back of the title page says Copyright 2018 Deborah Makarios. But the Creative Commons license means I’m sharing some of the rights.

So, for example, if someone wants to make a comic-book version of Restoration Day, they can do that without having to get in contact with me and get lawyers involved. But they have to say “based on Restoration Day by Deborah Makarios” or they’d be breaking the law as much as if I had it under All Rights Reserved. And they have to share, so if someone wants to make and sell t-shirts with bits from the comic book printed on them, they can’t stop them doing that.

Or someone might translate it into French, and someone else might make an animated film with the script based on the French version. It’s all allowed, with attribution, and the lines of attribution always point back to the original novel, which allows the work to reach audiences I myself have no point of contact with.

Easier Access Equals More Access

Interestingly, research has shown that novels published before 1923 (the US’s copyright cut-off) sell much better than books from most of the following decades, because people are free to publish and/or reuse them. Taking the US as our example (since it has one of the more restrictive copyright regimes), if you read a great book from 1921 and you want to write a spin-off, you can just go for it. The world is your oyster.

But if you read a great book from 1925 and you want to write a spin-off, you have to find who owns the copyright — and it’s probably not the name in the copyright notice, after all these years. (Not unless they were a child prodigy with remarkable longevity.) But you have to track them down and get their permission, or you’re breaking the law and heading for expensive trouble if the copyright owner (whoever that may be) ever discovers your spin-off title.

Copyright Laws in Different Countries

It’s worth noting that different countries have different copyright laws, and it pays to know the implications. In New Zealand, for example, works enter the public domain fifty years after the author dies, regardless of when they were published.

So The Chronicles of Narnia are in the public domain in New Zealand (C.S. Lewis died in 1963) but not in the US (because they were published after 1923). Conversely, some of P.G. Wodehouse’s early novels (Something Fresh, The Little Nugget, or Piccadilly Jim, for example) are in the public domain in the US (because they were published before 1923) but not in New Zealand (because P.G. Wodehouse didn’t die till 1975).

Brave New World for Authors?

So what does Creative Commons mean for us as writers? Is it a bold new world out there?

Yes and no.

- Yes, because we can absolutely publish books under CC licenses, providing a new way for our works to reach new audiences. If I can do it, you can do it!

- But also no, because not everyone is on board with the idea, and that causes difficulties for the author.

Difficulty #1: Self-Publishing Required?

For example, publishing your book under a Creative Commons license pretty much guarantees that you will be self-publishing, because very few publishing houses are prepared to countenance something new like this — something which they fear will hurt their bottom line. A notable exception is Free Culture, something of a classic when it comes to Creative Commons.

Written by Lawrence Lessig, one of the founders of Creative Commons, it was published in 2004 by Penguin Books. Brandon Sanderson, Cory Doctorow and Peter Watts are other authors who have published under CC licenses, but they are still few and far between.

Difficulty #2: Distribution Challenges

What has been, for me, the major downside of putting my book under a CC license is that a number of distribution companies refuse to handle CC books, and that has limited my publishing options.

What are the pros and cons with Creative Commons licenses? Click To TweetDraft2Digital, for example, will not accept CC ebooks for distribution, because, they say, vendors don’t like it. The vendors claim that people don’t like to pay for a book they then find they could have downloaded for free online.

This overlooks the fact that Amazon — to take the biggest example in the room — sells Public Domain (CC0) books all the time. They haven’t stopped selling the works of Jane Austen just because you can download them for free. Or Shakespeare. Or Dickens.

The really ironic thing is that CreateSpace (out of date now, but I haven’t been able to find the relevant information on the new setup) wouldn’t accept CC licensed books to sell in hard copy. Technology has advanced a long way, but I have yet to see someone download a paperback — although it’s probably only a matter of time.

Unfortunately, CC licensed works are sometimes lumped in with Private Label Right (PLR) works — something I’d never heard of, but which turns out to be a service where people can buy content they didn’t write along with the right to put their name on it. You can imagine how I felt on discovering that my desire to share the fruit of my hard work with other creative people had me lumped in with those who pay to take credit for other people’s work.

However, there are some places which do accept CC licensed works. IngramSpark does, which is why the paperback of Restoration Day is printed and distributed through their network (including on Amazon, ironically enough). They also accept CC licensed ebooks, but they insist on the author permitting DRM, which hampers legitimate users while barely inconveniencing pirates.

Smashwords, on the other hand, don’t allow DRM, but are ok with distributing CC licensed books. So there are options — just not as many.

Final Thoughts

Now you may look at all this and decide it’s not for you, and that’s fine. How your work is licensed is your choice, as it should be. But it should be an informed choice, not based on ignorance or, worse, misinformation.

I’ve accepted that being something of an early adopter in this area (probably the only area of my life in which I am, if we’re honest!) is going to cost me something in terms of options, but it’s a sacrifice I think is worth making.

The more awareness — and accurate understanding — there is of Creative Commons licenses, the more likely it is that the big players will be open to letting authors use them. And I believe that the more choice we have as authors, the better.

Please note:

All content by Jami Gold is Copyright Jami Gold, 2018. All Rights Reserved.

Post content above between ***** markers by Deborah Makarios is Copyright Deborah Makarios 2018, CC-BY-SA 4.0.

Attribution: ©Deborah Makarios, CC-BY-SA 4.0. Originally published on jamigold.com

*****

Copyright: CC-BY-ND, Esther Van Kuyk

Deborah Makarios was raised in the space between worlds and maintains an eccentric orbit.

She found her niche at the age of six when in short succession she read The BFG, her first Agatha Christie (Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?), and encountered her first P. G. Wodehouse (Something Fresh—saying “Heh! Mer!” is enough to make her laugh, decades later).

Her personal motto is tolle et lege—pick it up and read it—regardless of whether it is a Bible, a book, or a jar of home-made marmalade. Her mission is to write books, plays, and blog posts like cups of tea: warm, heartening, and restorative.

She believes in happy endings, the ultimate triumph of good over evil, and always having a clean handkerchief. It is, however, against her religious principles to believe in “normal.”

She lives among the largely unsuspecting populace of New Zealand with only two cats, and her brilliant, albeit marginally less eccentric, husband. She posts regularly on her website, and visitors are always welcome.

*****

Restoration Day by Deborah Makarios

Princess, pawn—or queen?

Princess Lily was born to be queen of Arcelia, where the land itself has life and magic growing in it. Yet she leads a pawn’s existence in the shadow of her guardians’ control. She dreams of the day when she will take her rightful place in the world.

At last her chance arrives, with a quest for the three Requisites of Restoration Day, the royal rite which renews the life of the land. But she’s been hidden away too long…

Stripped of all she thought was hers, Lily will need to do more than cross the board if she is to emerge triumphant as the queen she knows she must be. The land becomes both field and prize in a gripping game—and this time she’s playing for her life.

Pick up a copy in Paperback:

Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Book Depository

Or Ebook:

Smashwords

*****

Thank you, Deborah! This is fantastic information, and I had no idea about any of it. So count me in with the many writers who probably believed the myths on some level. Knowledge is good! *grin*

In fact, as I was reading Deborah’s post, I figured out a few changes I need to make with my worksheets. I also found it interesting that Deborah still charges for her book, as I assumed all work offered under a CC license had to be offered for free by the originating author.

According to the official CC FAQ:

“While many if not most CC-licensed works are available at no cost, some licensors charge for initial access to CC-licensed works—for example, by publishing CC-licensed content only to subscribers, or by charging for downloads.”

All that goes to show that we might have much to learn about the nuances of copyrights and exploiting our rights. As she said, the choices we make should come from a place of informed decision-making, not from ignorance or misinformation. *smile*

Want more information before making your decisions? Visit the Creative Commons website or check out the book Free Culture by Lawrence Lessig.

Have you seen or heard of the Creative Commons licenses before? Did you know what they were, or did you believe some of the myths? Do you think any of the CC licenses might apply to some of your work? If so, which one and why, and if not, why not? Do you have any questions for Deborah?

Pin It

Thanks for letting me guest-post, Jami! It’s been a real pleasure!

And if anyone has questions, I’ll do my level best to answer them 🙂

Thank you, Deborah! I’m so happy to have you share this information with everyone. 🙂

Actually, I have a question for you too. 🙂 As I mentioned in my outro/wrap-up of your post, I suspect the rights information on my worksheets should be changed.

Obviously, those are meant for people to download and use, and I definitely want to keep attribution (and preferably a link back to my worksheets page). But I’m not sure what else to even potentially “worry about” to think through what issues might be important or a concern.

What suggestions or insights do you have? How would you handle it (and why)? 😉 (Told you I loved your post. LOL!)

Glad you enjoyed it!

The questions to ask yourself with the worksheets are around what kind of use you’re happy for people to make of them.

For example, are you ok with people creating and/or distributing their own versions based on yours (providing they say it’s based on yours)?

Would you be ok with people using your worksheets for commercial purposes (without paying you)?

The Creative Commons site has a simple license-picker which asks you this kind of question and then presents you with the appropriate license based on your answers, so you could have a look at that, too.

I’ll be interested to see what you decide 🙂

Excellent! Thanks for the link! 😀

Great list and explanations. Thanks, both of you!

Thanks!

Wow, fascinating read! ? I use DepositPhotos, which has something similar to the Creative Commons, e.g. paying a fee to use an image for commercial purposes and having the right to modify the image, etc. But I didn’t know about the different nuances.

I’m curious what you think about the following scenarios:

1) People using GIFs from Google images for their blog posts. (The general assumption seems to be that it’s okay to use these GIFs as long as you’re not making money off of them. Similar thing to using images found on Google on your blog.)

2) People writing fanfiction on Wattpad, Archive of Our Own, Fanfiction.net, and other fanfic sites. Does mentioning a disclaimer like: “all rights belong to Nintendo” make it okay? Are such disclaimers necessary, though, since they are clearly fanfiction and not the author’s original fiction?

3) Folks making lyric videos on YouTube of popular songs. People often make a disclaimer: “All rights belong to [Name of Band/Singer]”. Is this sufficient, or is it still technically illegal?

Thanks!

1) There’s no guarantee as it’s not a question of you making money off them, but of money being made off of them. If your blog or website has ads, somebody is making money off those ads even if it’s not you. My WordPress blog has ads that only generate money for WordPress. I don’t see a dime of the money. The same applies for non-commercial uses of CC as some people make the usage to include nonprofits with Donate Now or PayPal buttons which aren’t normally considered commercial sites. 2) Fanfic tends to have its own set of rules which are often set by the holder of the copyright. For example, CBS has very stringent rules for allowing Star Trek fanfic. 3) It’s illegal. All that does is prevent from being sued for plagiarism. They are still in violation of copyright unless they are either doing it as parody/satire. A small enough portion might qualify as fair use, providing it meets the strict standards for fair use. At best, you are forced to go to YouTube Copyright School before being allowed to add videos. People really need to learn copyright basics before making websites, blogs, YouTube videos, etc. or risk what happened to a blogger who learned the hard way by being sued. She settled before the case reached judgment, but she may have paid more than necessary. She made all the mistakes that many people make about copyright. Here’s a quick cheatsheet for U.S. copyright, but it doesn’t… — Read More »

Hi Sieran!

Sorry about the late reply – I thought I was getting emails of all the comments but it appears not to have worked out that way.

The great thing about Creative Commons images is that you don’t have to pay a fee! But you do need to check whether the specific license allows modifications, commercial use etc.

As for the three examples you use, it’s hard to say. They’re likely illegal, as providing a reference to the original artist still doesn’t give you the right to use their work. But legally, it depends on whether it falls under “fair use” or not, and frankly that’s a grey area until it’s tested in court.

Which is why I stick to Creative Commons works! Hope this helps 🙂

On the non-commercial CC, you have to be careful as some who attach it to their work define commercial as having anything on your website/blog that generates income of any kind even if you don’t make money on it. On my blog, the ads don’t generate money for me, but do generate money for WordPress. Always best to ask the person who has the NC CC what they mean by NC. You also have to watch for things like Wikimedia which has a number of CC images that aren’t CC as they were added by people who assumed something was in the public domain when the images weren’t in the public domain. Too many people assume that if it’s on the Internet, that’s automatically in the public domain. If that’s not bad enough, people assuming that “fair use” applies when it doesn’t. Fair use is a very restrictive exception as well as not being a universal concept in many countries. Also, from a legal standpoint, I have yet to see a court case where SCOTUS has ruled on the legality of CC since it’s not covered under copyright law. I suspect at some point, it will become a SCOTUS case where an heir takes exception to a parent who used CC. Let’s suppose my child takes exception to a book that I wrote with a CC-public domain license. The book becomes a rousing success; I die; then my child wants to benefit financially from the book. No telling as to… — Read More »

Thanks for chipping in! Copyright law is a murky world, all right.

No worries! Thanks for your replies! Yes, it’s a murky area for some of these things. D: And just because “lots of people” do it, doesn’t make it legal. (For example, people buying pirated VCDs back in the day.)

[…] very kindly invited me to contribute a post on Creative Commons licenses, and here it is! Pop across and have a look […]

[…] An Authors’ Guide to Creative Commons — Guest: Deborah Makarios […]