Antagonists: The End-All-Be-All of Our Story — Guest: Kristen Lamb

As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, I’m currently dealing with more health-related difficulties, and I’m going through extra medical treatments in an attempt to salvage my rebuilt jawbone before my surgeon decides to rip out the last year of work due to instability. On the good side, I think I finally beat my cold. *smile*

To lighten my load, with her permission, I’m sharing some of Kristen Lamb’s insights on antagonists: what they are, why they help define our story, how to strengthen them, etc.

Two weeks ago, we started by exploring what antagonists are, and specifically what a story’s main antagonist is, what she calls the Big Boss Troublemaker (BBT). As she mentioned in that post, antagonists aren’t always a person or a villain.

Sometimes, we’ll say that a character is their own worst enemy, such as the “man versus self” story premise, and then use proxies of the BBT to provide a face for the opposition. Kristen also gave us an in-depth example of how outside characters can be a representation of our protagonist’s internal issues.

Today, we’re going to explore how antagonists—especially our BBT antagonist—create our story. Kristen’s post will help us determine the right beginning and ending for our story, as BBT antagonists create the conflict that forces our protagonist to grow.

Please welcome Kristen Lamb once again! *smile*

*****

Understanding the Antagonist:

The Key Ingredient for Dramatic Tension

Conflict is the core ingredient to fiction, even literary fiction. Conflict in any novel can have many faces and often you will hear this referred to as the antagonist.

The antagonist is absolutely essential for fiction. He/she/it is the engine of your story. No engine, and no forward momentum. Like cars, plots need momentum or they are dead.

The antagonist provides the energy to move the story forward. Antagonists generate genuine drama. No antagonist, and we get the crazy, unpredictable cousin of drama known as melodrama.

The BBT Antagonist Defines Our Story

The Big Boss Troublemaker (BBT) is whoever or whatever causes the protagonist’s world to turn upside down. The BBT creates the overall story problem that must be solved by the end of Act III. This is also who or what must be present at the Big Boss Battle.

There is no story without the Big Boss Troublemaker. Period. The story is the BBT’s agenda.

What defines our story? It's the antagonist's agenda. Click To TweetNo Buffalo Bill, no Silence of the Lambs. No Darth Vader, and Skywalker doesn’t have a Death Star to destroy. If Joker was a choir boy, Batman’s life would have no meaning.

In Finding Nemo, the Big Boss Troublemaker was Darla the Fish-Killer. Though we only see Darla a few minutes out of the entire movie, it is her agenda that creates the problem.

If Darla wanted a kitten for her birthday, little Nemo would have been safe at home. It is also Darla’s propensity to kill her fish that creates the ticking clock in the race to save Nemo.

The Stronger Your BBT, the Better

The BBT doesn’t have to be terrifying, but he/she/it must be powerful. Think of Rocky. If his big fight was against the band nerd from three flats down, it would make for a lousy story/movie.

In the beginning, our protagonist should be weak. If pitted against the BBT, your protagonist would be toast…or actually more like jelly that you smear across the toast.

One of the biggest problems I have with new writers is they shy away from conflict. New writers tend to water down the opposition.

This is natural. As humans, we really don’t like a lot of conflict…unless you happen to be a regular on the Jerry Springer Show.

Want a strong story? Create a strong antagonist. Click To TweetIt is natural to not like conflict, but good fiction is the path of greatest resistance. The bigger the problem, the better the challenge and thus the greater the hero. The best stories are when we look at the opposition and ask, “How can the protagonist ever defeat this thing?”

A fantastic example of this is the movie The Darkest Hour. I spent over 2/3 of the movie wondering how on earth humans would survive, let alone have a fighting chance. This movie was terrifying, not because of a lot of blood and gore, but rather because the opposition was so overwhelming it seemed there was no hope of winning.

I’ll warn you that the movie is frightening, so those who dare can check out the trailer here. The trailer alone is enough to show what I’m talking about.

Developing a Story? Start with the BBT

A couple years ago, Bob Mayer, NY Times and USA Today Best-Selling mega-author, taught me a technique that changed everything about the way I wrote. Bob advised that I start thinking of the antagonist first.

Initially, I was resistant. I mean, I wanted to construct my heroine. She was far more fun. But, as I would soon learn…that was backwards thinking.

The antagonist is the entire reason for the story. No antagonist and no core story problem in need of resolution.

Construct the Big Boss Troublemaker first. Trust me. You will thank me (and Bob) later.

Antagonists are the Alpha and the Omega

Once we understand the antagonist, narrative structure falls into place with far less effort. The antagonist is responsible for the Inciting Incident (beginning) and the Big Boss Battle (the end).

Story Beginnings: Antagonists as the Alpha

When we know our antagonist, it is easier to find a beginning point. When we understand what the antagonist wants, then it is easier to pinpoint where and how his life intersects with our protagonist.

The opening of our story—the Normal World—shows us the protagonist’s life as it would have remained had the antagonist never come along to disrupt things. Normal World grounds us and gives us a chance to become invested in the protagonist. We need to connect if we are going to spend the next 80-100,000 words caring for this character.

Normal World hints that all is not well. It doesn’t hang us over a cliff or a tank of sharks or have us in a hospital weeping over a lost loved one. That is melodrama.

The Inciting Incident is that point where the agenda of the antagonist intersects the life of the protagonist. The Inciting Incident is that event that offers the possibility of change.

Story Endings: Antagonists as the Omega

When we understand the antagonist and his agenda, it is far easier to write great endings.

In Star Wars, we knew Darth’s plan involved the Death Star. Thus, the ending logically would involve the Death Star getting all blowed up, right?

In Romancing the Stone, the bad guys kidnapped Joan Wilder’s sister in order to get the jewel. Thus, even if we had never seen the movie, it would be easy to extrapolate that the ending likely involves rescuing a sister and making sure bad guys go to jail and don’t end up with the jewel.

What Is the Big Boss Troublemaker’s Agenda?

Our beginnings might change a dozen times or more before we make it to the final draft. If you are beginning a book, my advice is that you write out your antagonist’s agenda:

- What does he want?

- Why does he want it?

- How does he plan on getting what he wants?

Remember that the antagonist, in his mind, is not the bad guy. This will help give your antagonist dimension. The antagonist is the hero in his own story.

Hannibal Lecter felt he was doing society a service by eating the less desirable members of the species. It is his warped justification for his actions that makes him even more fascinating.

Antagonists are not always wrong; their goals just conflict with the protagonist and disrupt her life and force change.

For instance, the antagonist in Steele Magnolias is the daughter, Shelby. What is her agenda? Have a baby despite having severe, life-threatening diabetes. That is a noble goal that isn’t necessarily wrong.

Why does this make Shelby the antagonist? Because, if Shelby had been happy to adopt, then M’Lynn’s (mom-protagonist) life would have remained the same.

When we understand Shelby’s plan—have a baby despite life-threatening diabetes—then plotting becomes far easier. At the end, there must be a baby. Whether that baby lives or dies is up to the creator.

Your protagonist will be reacting to the antagonist’s agenda for roughly 75% of your story. It is only in the final act that your protagonist will transition into a hero and will start gaining ground.

This is why, when we begin a novel, it makes sense to figure out the ending first. Then, plotting becomes much easier in that we know how and where the story ends. Then plotting is just a matter of getting the protagonist from point A to point Z.

*****

Kristen Lamb is the author of the definitive guide to social media and branding for authors, Rise of the Machines—Human Authors in a Digital World. She’s also the author of #1 best-selling books We Are Not Alone—The Writer’s Guide to Social Media and Are You There, Blog? It’s Me, Writer.

Kristen Lamb is the author of the definitive guide to social media and branding for authors, Rise of the Machines—Human Authors in a Digital World. She’s also the author of #1 best-selling books We Are Not Alone—The Writer’s Guide to Social Media and Are You There, Blog? It’s Me, Writer.

Kristen has written over twelve hundred blogs and her site was recognized by Writer’s Digest Magazine as one of the Top 101 Websites for Writers. Her branding methods are responsible for selling millions of books and used by authors of every level, from emerging writers to mega authors.

*****

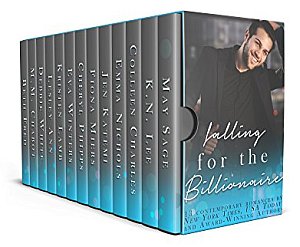

Kristen also just released a new romance novella, Deadline, available in a box set anthology (usually she’s a thriller author, so I’m excited to see how she tackles romance! *grin* ):

Falling for the Billionaire: A Contemporary Romance Boxed Set

Legendary billionaire Atticus Black longs to escape his bad boy reputation from his role on the realty TV show “Bosses from Hell.” He yearns for solitude, and invests in a small remote boomtown in South Texas.

Legendary billionaire Atticus Black longs to escape his bad boy reputation from his role on the realty TV show “Bosses from Hell.” He yearns for solitude, and invests in a small remote boomtown in South Texas.

When he meets owner of Titan Construction, Sian MacIntyre, little does he know this feisty gal has an even harder head under that hardhat. She’s smart and striking and not at all impressed with him or his money or his “celebrity hands.”

But, when a dead woman is discovered on the building site, murdered with Sian’s sledgehammer and in possession of Atticus’s cell phone, their fates are cemented together. Both are prime suspects for murder and the focus for media mayhem.

They didn’t ask to be targets or a team, and never asked for what they never knew was even possible…love.

Buy Deadline and all the Falling for the Billionaire romances in one box set!

*****

Thank you, Kristen! And as always, I can’t express my gratitude enough for your help during these few weeks!

(Speaking of the awesomeness of Kristen, did you see the mug she sent to cheer me up after my depressing test results? I have the best friends. *hugs to all of you*)

I love Kristen’s explanation of how truly understanding our BBT antagonist and their agenda reveals the shape of our story. If we know how the BBT intersects with our protagonist, we’ll know when our story kicks off and how it ends.

Even if we’re a pantser, we can use the knowledge of our antagonist to feel our way through the story. We’ll know the gist of what our hero needs to overcome.

We’ve talked before how knowing our ending can help both with our character’s arc and with plotting out our story. So this information is the missing piece for how to develop our story: come up with our story’s ending by understanding our BBT’s agenda. *smile*

Do you agree or disagree that antagonists create our story? Do you think starting with the antagonist might help with story development? Do you know who the BBT is for your story? Do you know their agenda? Does knowing that help you figure out if your story is starting or ending in the right place?

Pin It

Construct the antagonist first – Just reading that, I know it is right and I have been doing it wrong. In particular, I have been doing the BBT second.

this is so helpful! thank you!

The antagonist has to be part of the story, but I don’t recommend going OTT about it. I’ve just finished writing and editing a crime book in which the antagonist is either someone for whom we can feel empathy and sympathy, or someone we don’t meet. This has been fun and a challenge. I knew the outcome from the start, but it keeps my protagonist guessing. Just shows that you can write antagonism without going over the top. This would not suit every genre – thrillers need a much stronger threat force – but I think my readers are going to be puzzle solving types, they should enjoy it.

[…] The End-All-Be-All of Our Story […]

[…] female protagonist) can’t travel, and Kristen Lamb adds to her series on antagonists with antagonists: the end-all-be-all of our story and antagonists: what’s driving our […]

[…] antagonists that get in the way of protagonist, but avoid boring or cliché […]