Editing Tips: Top 3 Writing Craft Issues — Guest: Naomi Hughes

Editor Naomi Hughes is here again this week with the third—and last—post in her series about the top issues she sees in story and writing craft. If you missed my introduction before, she’s been joining us for a series of posts, each concentrating on a different stage of editing.

In her previous posts, Naomi first focused on the revisions that address the big picture of storytelling. That level of editing is often called developmental editing but can also be called content editing or structural editing.

Her second post focused on the revisions that strengthen scenes. We’ll usually have to ask the right questions of our developmental or line editor to make sure one (or both!) of them is looking at this level of fixes, as most editors don’t mention these issues as separate edits.

Today she’s sharing her insights on the edits that improve our writing craft: line edits.

However, as I’ve mentioned before, the titles editors use to explain their skill set can be a bit imprecise, and nowhere have I found this to be more the case than with line editing. When I was searching for a line editor for my work, the majority of samples I received focused more on copy editing than line editing.

Naomi’s going to cover the differences between those editing stages below, so let’s join her as she shares the most common issues she sees at the craft level of line editing. With her help, we’ll know what to look for—and avoid—as we try to make our writing smoother, stronger, and clearer.

Please welcome Naomi Hughes! *smile*

*****

The 3 Most Common Writing Craft Issues

Hi again! I’m Naomi Hughes, young adult writer, editor, and yet again the commandeer-er of Jami Gold’s blog for the day (huge thanks to the commenter who told me how to make my own pirate tricorn hat, because YES).

This is the last in a series of posts I’m doing about the most common problems I come across during each of the three main stages of editing—and how to fix them. Up today is my personal favorite, one of the least-known and most-misunderstood stages: line editing!

What Is Line Editing?

Line editing is the final stage of revisions—other than copy editing, which deals with typos and proper grammar (and which people commonly confuse with line editing, though they’re very different).

By this point, you’ve got all edits pertaining to the story finished, and now it’s time to make sure that the writing itself is sharp and honed and allows the reader to be completely immersed in your story.

Because it deals with the nitty-gritty details at a sentence-by-sentence level, line editing is usually very extensive and can include 1,000-3,000+ tracked changes. Getting through 10 pages tends to take line editors about an hour.

Line editing is one of my favorite stages because it’s so rewarding, especially if I’ve already worked with the author on prior drafts of the story. I love watching something go from a mass of beautiful, lumbering, unwieldy potential to a sharp, swift instrument of fulfilled intent.

In my work with line editing, I tend to run across several very common problems. Without further ado, here are my notes on what they are and how to fix/avoid them:

#1: Metaphors That Don’t Work

It’s a common misperception that “good” writing must include lots of metaphors. And while some of the most gorgeous prose I’ve ever read (The Star-Touched Queen and The Winner’s Curse are top examples) does indeed have some truly beautiful metaphors, there are many ways to write well, and not all of them use that technique.

The ones that do use metaphors as a signature technique use them very meaningfully, and they typically fulfill one or several of these purposes:

- Comparing an Unknown to a Known:

This is the most workmanlike way to use a metaphor—you’re comparing something the audience can’t easily picture to something they can, so that you can quickly make your meaning clear without getting super boring and explain-y.

- Giving New Insight/a New Way of Looking at a Story Element:

These metaphors are kind of like one of those pictures you give people that looks like a devil, and then you tell them to look for the profile of an angel instead and then they gasp because the picture is really both things at once—and now they can never again look at that picture and see only a devil.

Great metaphors give the reader an insightful new way of looking at something, a subtle shift in perspective that often also illuminates or ties to a deeper story theme. The way I see some writers trip up here is because they think that they must have a deep, meaningful, perspective-changing metaphor on every page—but again, less is more here.

Think of metaphors (and particularly this type of metaphor) as a highlighter: if you use it infrequently, it’ll jump out at readers and feel special. But if you highlight every single page, soon it’ll feel repetitive and annoying and grandiose in a silly, self-referential way.

- Setting the Tone:

Although this is a vital use for metaphors, it’s another spot where I see a lot of writers go overboard.

In a single paragraph, I’ll see mentions of the moon reflecting like a spotlight from a glass shard that also looks like a monster’s tooth, and letters splashed across a door bright as blood, and fog that creeps like a… creeping thing.

For setting the tone, subtlety goes a long way. Try to use fewer metaphors and pick ones that give you the most bang for your buck by fulfilling several of these purposes at once.

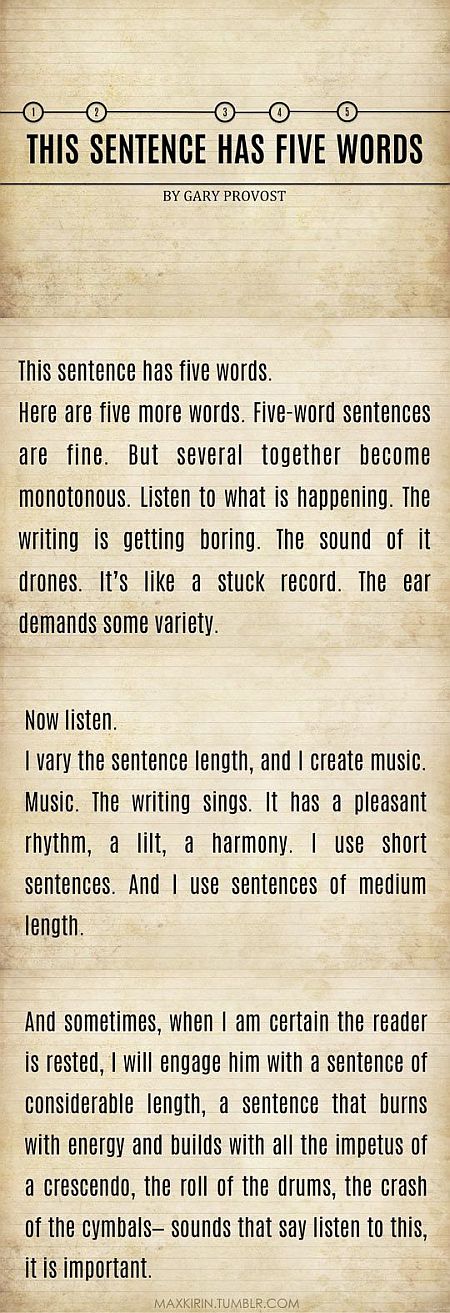

#2: Repetitive Sentence Structure

When line editing, I often see repetitive sentence structure. Clause-comma-clause is the one I see most frequently, though I also see repeating single-clause sentences.

This gets monotone fast, because the rhythm feels flat. It starts to drone, and the reader gets bored.

(See? Boring.)

Here’s the example I always give:

(Note from Jami: Here’s more about giving our writing rhythm.)

#3: Filter Words

This is a sub-type of showing vs. telling. Instead of laying out a scene and letting us watch it unfold and come to our own conclusions (which would be showing), filtering means you’re telling us information about what the POV character sees and hears and feels.

For example: “She heard footsteps behind her.”

The problem with filtering is that you’re using your POV character as a middle man; you’re forcing readers to remember that someone else, and not readers themselves, is the one watching everything unfold. This prevents us from having a more immersive experience and it distances us from your story.

Luckily, filtering has an easy fix. All you have to do is chop out the filter words and let the scene stand for itself:

“Footsteps pounded on the path behind her.”

As a bonus, once you nix the filter words you can use much more evocative verbs (like “pounded”) in their place.

(Note from Jami: Here’s a great post with common filter words by Janice Hardy if you want more information.)

That’s it! I’m so glad I got to come hang out with you guys. It’s been a pleasure and an honor, and I hope to see you all around Twitter (where I spend way too much time) in the future—I’m @NaomiLHughes.

Huge thanks to Jami for letting me chat with you about the different stages of editing!

*****

Naomi Hughes is a freelance editor and an Assistant Editor at Entangled Publishing. She’s also a writer, and loves to hide sneaky fandom references (Doctor Who! Pacific Rim! Sherlock!) in her quirky young adult stories.

Naomi Hughes is a freelance editor and an Assistant Editor at Entangled Publishing. She’s also a writer, and loves to hide sneaky fandom references (Doctor Who! Pacific Rim! Sherlock!) in her quirky young adult stories.

She lives in the semi-rural Midwest with her husband, the most adorable preschooler on the planet, and several pets who are all named after characters from Avatar: The Last Airbender.

You can follow Naomi on Twitter at @NaomiLHughes, where she frequently hosts giveaways and chats about publishing advice, and find her at her website, where she offers editing help for everything from queries and synopses to submission packages and full manuscripts.

(*psst* Note from Jami: Naomi also shares a fantastic Revision/Plotting Checklist on her site.)

*****

Thank you, Naomi! It’s been wonderful to share your insights with my readers throughout this series, and I agree with you that line editing is often misunderstood and unappreciated.

My first mentor-editor loved line editing like Naomi does, and even though that editor never worked on my writing aside from an example paragraph here and there, I absorbed everything I could from her during my climb up the learning curve. In other words, I hope Naomi’s examples illustrate why this stage of editing can deeply affect readers’ impression of our work.

Yet, as I mentioned in my introduction, we have to be careful about just taking an editor’s word for it that their strength lies in line editing. We should be very picky about who we let line edit our work, especially as we need to make sure our editor is a good match for our voice. (Many line-editing changes—rhythm, sentence structure, etc.—are voice-dependent.)

Let me also add two bonus issues that affect the clarity and strength of our writing craft beyond the grammar and spelling changes of copy editing:

- Missing Transitions/Antecedents:

Sometimes when our work feels choppy, it’s because we’re not leading readers through the journey (either plot events or emotional), and we need to smooth out the flow with transitions (or rearranging ideas).

Similarly, whenever we use pronouns, we need to ensure that it’s clear what he/she/it we’re referring to.

- Repetitive Ideas/Words:

Sometimes as we’re drafting, we might take a paragraph or two to finally uncover our point—the meaning we want readers to take away. In later edits, we should cut those repetitive-but-not-quite-right sentences and paragraphs.

Also, we can end up with word echoes, as our characters nod, or smile, or shrug multiple times a page. Jordan McCollum’s gesture crutch macro helps me catch most of these echoes. (Here’s my post about using macros.)

Depending on our copy editor, we might receive feedback on the two above issues from them as well, but we can’t have too many eyes looking at our work. *grin*

Hopefully, these tips for what to watch out for will help our work flow more smoothly and more strongly grab our readers’ interest. Clunky, unclear, and weak sentences and paragraphs will slow down our pacing and weaken our hold on our readers, so it’s important to strengthen our story line-by-line. *smile*

P.S. Don’t miss the rest of Naomi’s series, covering developmental edits and scene edits.

How familiar are you with line edits? Are you able to fix most of these issues on your own, or do you need someone to point out issues? As a reader, have you noticed problems with stories at the line-edit level? Do you have any tips to add for how to find or fix these issues? Do you have any questions for Naomi?

Pin It

I’m in the polishing stage of my latest wip, and these suggestions were just what I needed. Many thanks!

Love this post. Naomi certainly seems to know her stuff.

I find line editing the most frustrating part of the process; and then when I think of the perfect answer to the strange way I’ve worded something, also the most satisfying.

I use Grammarly and Pro-Writing Aid amongst other software before my work goes to human editors and some of the advice, whilst invaluable, makes me feel like an utter dunce!

“You have started six sentences in a row with the same word.” Really?! Again?!

Thanks for the post. I can never read enough tips from experts.

Best regards,

Michael

Greetings,

Thank you Naomi Hughes and Jami. Currently in the midst of revision. I loved the descriptions of editing types. Now at least I understand the terms.

The information about metaphors and rhythm is excellent. I guess rhythm in writing, like rhythmic activity with people (kissing a woman comes to mind), better not be flat or boring. Definitely not flat. Because flat is totally boring.

And the take away is: kiss better, write better.

Stay Well,

Donovan

Useful tips! I tend to read my text silently for flow; and having recently heard my husband read someone else’s book aloud, I’m now extra-alert for conversations where it’s hard to tell who is saying what! Just because the author can hear the voice in their head, doesn’t mean the reader can.

P.S. You’re welcome for the hat tip! I’ve been meaning to get my summer writing hat all up and trimmed, but summer hasn’t really happened yet 🙁

I especially liked the part on metaphors. Haha, I sometimes use metaphors for humorous effects ^^ , since I write comedy in my stories.

Humor can also be a fun and effective use of metaphor! ?

Thanks, Naomi and Jami! I’ve been confused about the difference between line and copy edits, and also about the difference between “content” and “structural” in reference to editing. Of course when a good editor (like my lovely editor) does all of it, it isn’t really necessary to know the terms for what she’s doing; but it IS necessary to know them when talking or writing about the process(es). So thank you for clearing my confusion up!

[…] Editing Tips: Top 3 Writing Craft Issues — Guest: Naomi Hughes | Jami Gold, Paranormal Author […]

[…] mix sentence and paragraph beginnings to avoid repetition or monotone rhythm […]

[…] to mix sentence structure (subordinate phrases, subject/verb/object, compound sentences, etc.) to avoid sense of repetition […]

[…] Editing Tips: Top 3 Writing Craft Issues — Guest: Naomi Hughes (problems with metaphors, repetitive sentence structure, and filter words) […]

[…] P.S. Don’t miss the rest of Naomi’s series, covering scene editing and line editing. […]