Does Every Story Need Conflict?

It’s time for another one of my guest posts over at Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi’s Writers Helping Writers site. As one of their Resident Writing Coaches, I’ve previously shared:

- insights on how to approach an overwhelming revision

- how to increase the stakes (the consequences for failure) in our story

- 7 ways to indicate time passage in our stories (and 2 issues to watch out for)

- how to translate story beats to any genre

- how and why we should avoid episodic writing

- how to find and fix unintended themes

- how “plot” holes can sneak into our characters and worldbuilding

- how TV shows can help us learn to hook our readers

- what we can learn from stories that successfully break the rules

- how to ensure revisions aren’t creating rips in our story

- how to create strong story goals that won’t slow our pacing

- how to keep readers supportive through our characters’ changes

- how to use bridging conflict to kick off our story’s momentum

- how to create the right pace for our story (and make it strong)

- how to make the “right” first impression for our character

With this turn for another coaching article at WHW, I’m exploring whether every story needs conflict. We often assume the answer is yes, but what if our story idea features low — or even no — conflict? Is our story doomed? Let’s take a look…

Conflict: The Usual Advice

When I ask the question “Does every story need conflict?” the usual assumption is probably yes. We might even throw a “duh” into our answer for good measure. *smile*

In fact, we often study how adding conflict will help our story’s pacing or tension or character arc. We layer internal and external conflict to round out our story and character. Or we experiment with tweaking the stakes of our story’s conflict to increase the consequences of failure.

Without conflict, our character’s success wouldn’t be in question. Without the threat of failure, our characters wouldn’t have strong motivations to avoid the negative consequences. And readers wouldn’t have the same compulsion to turn the page and discover “What happens next?”

Conflict: The Usual Approach

In novels and movies, especially in genre stories, we’re used to the idea of needing conflict—and lots of it—in our stories. The reason is that most storytelling we’re used to focuses on character goals and story problems.

Is our story doomed if the idea doesn't lend itself to include conflict? Click To TweetWith a story problem, characters have goals to overcome the problem and “win.” They win the love interest, they beat the villain, they earn the promotion, etc.

That story structure requires conflict because without it, the story would be over—with the character succeeding in their goal—before it even got started. Conflict is what gives the story its shape between the beginning and the ending.

We use conflict, such as obstacles and setbacks, to reveal our characters: their priorities, fears, growth, etc. Their successes and failures reflect on them and make readers invested in the story.

But that’s not the only way to tell stories. In fact, some stories contain no conflict at all.

Wait…Stories without Conflict?

Obviously, using conflict to reveal character is not the only way to learn about someone, fictional or not. And not every story centers on characters anyway, as some focus more on themes, morals, journeys, etc.

In fact, if we stop and think about other types or mediums of storytelling, everything from comics to video games, we might realize that the types of stories that readers find enjoyable is far broader than we often see in our fiction-writing genres.

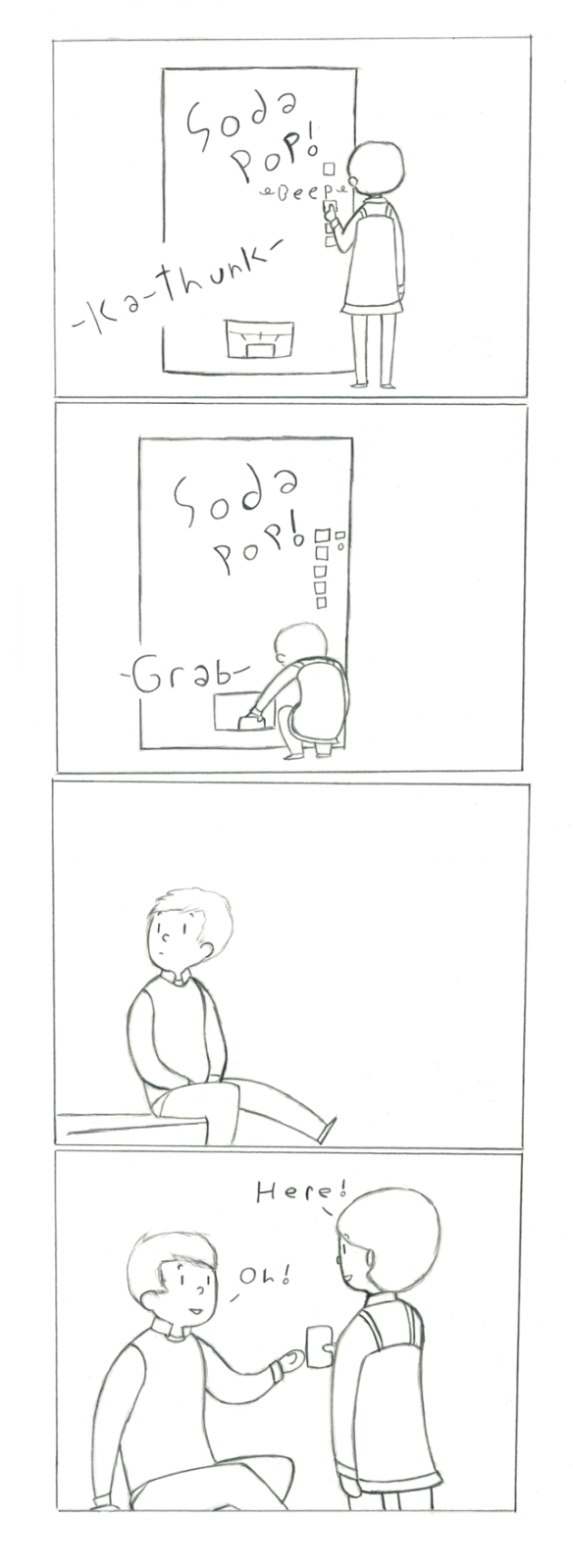

For an example of the diversity in storytelling that we might forget exists, here’s a no-conflict story based on the kishōtenketsu structure:

So not every story fits with the usual advice about conflict. But there’s a risk, especially with audiences who expect the usual dramatic narrative structure for our stories.

How do the exceptions get away with a different approach? And how can we know if our story might fit with those exceptions (or if we’re just falling for wishful thinking because coming up with conflict is hard)?

Writers Helping Writers: Resident Writing Coach Program

No Story Conflict? Explore Your Options

Other than simply trying to add more conflict, what are our options when our story doesn’t lend itself to the usual conflict advice? Come join me at WHW above, where I’m sharing:

- how the well-known dramatic-arc structure doesn’t work for every story

- 6 examples of story structures with a different approach to conflict

- what makes a story a story (hint: it’s not conflict)

- how stories can incorporate change outside the story itself

- a closer look at the kishōtenketsu story structure

- how alternate story structures won’t automatically “fix” our low/no conflict stories

Can you think of stories with low or no conflict? How did the story keep the audience invested? Do you struggle with adding conflict to any of your stories? Do you think they might fit in an alternate structure (and if so, why)? Do you have any insights or questions about using alternate approaches to conflict in our stories? (My WHW posts are limited in word count, but I’m happy to go deeper here if anyone wants more info. *smile*)

Pin It

I can see where this would work for short – possibly VERY short stories – but a novel-length book? The cartoon, without conflict, is to me “Okay, she got the guy a drink.”. So? Then I read the WHW post, and it made more sense. It’s not a lack of conflict – it’s just recognizing that conflict doesn’t have to be blatant. It’s simply change. Kinda like “acts” in story structure. We may think we’re writing 3-act or 5-act – in reality, we could have 10 acts or 20 acts. It really just means there’s a “change” that the character(s) can’t retreat from.

I don’t know. I seriously think too many (new) writers get bogged down with all the technical stuff. Relax and just tell me a story. 😉

Hi Star,

LOL! I hear you — as long as readers are engaged some how, some way, the story works. 🙂

BTW, some of the examples of kishōtenketsu I saw from various sources were the Japanese animated movies Kiki’s Delivery Service and My Neighbor Totoro (both by Hayao Miyazaki, who’s also known for Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, and Princess Mononoke). I haven’t seen these whole movies (just pieces), so I’m not an expert, but from what it sounds like, these movies aren’t conflict-less, by any means, but they do take a different approach than we’re used to from Western stories.

I watched Howl’s Moving Castle with my son eons ago – and no, it definitely was NOT conflict free! And it was a lot closer to western-style conflict than just “changing circumstances”. 😉

Hi Star,

Yes, I haven’t seen Howl’s Moving Castle listed as an example, so I don’t know if it follows the kishōtenketsu structure or not, but either way, I don’t think the structure needs to be conflict-free. It’s just that it can approach conflict a different way. 🙂

Hey just wanted to slip in and point out that Howl’s Moving Castle was written by Diana Wynne Jones, i.e. it’s a Western story. Miyazaki only adapted her novel into a movie. I loved both the book and the movie, btw, so I’m not slamming it. In fact, I feel like some have the misconception that this is a critique on Western narratives, but really, this post was just to point out the alternative narrative structures. Neither narrative style is superior to the other.

Hi Sieran,

Thanks for sharing that detail, as I wasn’t aware of that history of the story. 🙂

Haha np. With Howl’s Moving Castle, this was one of my rare triumphant moments of “I read the book before it was cool” XD I mean, it was always cool, but I was very thrilled when Miyazaki chose to adapt a book I really enjoyed reading.

Ooh, I can comment on Kiki’s Delivery Service and My Neighbor Totoro, since I watched them multiple times in my childhood, haha. Hmm, I wouldn’t say there is no conflict at all, but the “conflicts” seem relatively minor, e.g. a tiny argument between these two characters, a brief disagreement between these two other characters, etc. However, when it comes to the big, over-arching plot, the change is more of a twist than a conflict. Kiki used to have this life, and suddenly something happens to her, and now she lives a very different life. The protagonists in My Neighbor Totoro also have a dramatic life change after certain things happen to them. Considering how popular these two films are, Miyazaki definitely managed to engage the attention of many viewers. (My Neighbor Totoro is my favorite Miyazaki film.) Aside from the appeal of this dramatic life change, both films also have a before-and-after contrast when it comes to an interpersonal relationship. Before the events, the heroine looked down on this guy. But after the events, she grew to like him and they became lovers. I would still say that this (slight) enemies-to-lovers plot, is a small part of the story, since the dramatic life change takes up much more screen time. Yet, I feel like the interpersonal relationship change, stirs up the curiosity and interest of some viewers. When I saw the last frame in the Kishōtenketsu comic, I was immediately curious about the characters’ relationship. Are they lovers, friends, siblings,… — Read More »

Hi Sieran,

Thanks for chiming in with more insights into those two movies! 🙂

I was so happy to see these two examples listed, especially as I had never thought of them as having an alternative narrative structure before.

**SPOILERS AHEAD FOR MY NEIGHBOR TOTORO AND KIKI’S DELIVERY SERVICE**

For My Neighbor Totoro, it’s basically “They met Totoro. Now their life has changed.” For Kiki’s Delivery Service, it’s “She lost her witch powers. Now her life has changed.”

From these examples, you can see that though the major twist isn’t exactly a conflict, they are still really huge, impactful events that completely change the protagonists’ life. This before-and-after contrast, is probably one reason why the story is so attention-grabbing. I read somewhere that contrast appeals to us, and that’s why many works of art, not just stories, rely on contrast to catch our attention. Contrast is riveting.

Hi Sieran,

Oh yes! Contrast is huge, and another way of looking at the change our story needs as well. So interesting–thanks for sharing!

We can write YA books in which there is no real conflict, but the theme is coming of age. My two latest books are about young teens coming of age during the coronavirus lockdown.

Hi Clare,

Great example! Yes, coming-of-age stories are often different than the usual expectation when it comes to conflict as well. Thanks for sharing! 🙂

“The Slow Regard of Silent Things” by Patrick Rothfuss didn’t have conflict. I purchased it because I was desperate for the sequel to “The Wise Man’s Fear”. I was disappointed. It contributed nothing to the series and was about the wanderings and ramblings of a strange girl who lived in the nooks and crannies of a university. However, it was interestingly written. The girl’s oddities were intriguing. I wouldn’t go so far as to recommend it. But I wouldn’t say it was terrible either.

Hi Dawn,

Yes, that’s a great point. Just because we might be able to “get away with” a low/no conflict story by following a different structure doesn’t mean readers — especially if they’re expecting a more traditionally structured story — will find it satisfying or enjoyable.

That’s why I wanted to caution writers that while different structures or approaches to conflict might be an option, we still want to ensure that’s what’s best for the story we want to tell rather than just be a reflection of our lack of creativity. 🙂 Thanks for sharing!

Hey Jami, Wow this was fascinating! I went to Google some examples of the above alternative story structures. Some narrative structures were harder to find examples for (esp. the Robleto), or maybe my Googling skills just aren’t the best. It strikes me that even some Western stories use some of these alternative narrative structures. The Rashomon TV Tropes page you linked us to, has a load of examples from different sources, including novels written by Western authors. Huit Femmes (a French movie) sounds like a Rashomon narrative too, where eight women tell their version of what happened, what they believed or claimed to have happened, and how the man might have died (or been killed). There are some skirmishes, arguments, and other interesting interactions between the women, but the main intrigue of the movie is how we are told eight different versions of what happened, and we try to figure out who was lying or concealing something. Or you could say that everyone was lying to some extent, based on their personal motives. Omg I love fanfic fluff! I’ve been reading a fluffy fanfic lately on Nora Sakavic’s All for the Game trilogy (the first book is called The Foxhole Court). Each chapter is like an episode, though the episodes are all connected. The chapters are mini stories on things that happen while the friends are out at their summer vacation together. The fanfic ships my OTP, Neil and Andrew, so in each chapter, we see fluff happening. We see… — Read More »

Hi Sieran,

Yes, I didn’t find much about Robleto either, but it was an interesting enough idea–reminding me of storytelling poems–that I wanted to mention it. 🙂 And yes, not all of the alternative structures are specifically non-Western, but they all take a different approach to conflict than what seems to be the default structure for Western stories.

(Thanks for sharing the Chinese name for the kishōtenketsu structure! I hadn’t seen that anywhere.)

Interesting! Yes, in many ways, rather than the stereotypical idea of conflict many of these stories simply show characters adapting or dealing with situations. That’s another perspective of change that we can keep in mind. Thanks so much for sharing all your insights! 😀

“no-conflict story based on the kishōtenketsu structure:”

Is it a story? Or just a scene? And

Is there a suspense arc? Or is it rather boring?

That is why a story indeed needs a conflict.

Conflict here could be:

Person one does not like Person two, but Person two needs help. An internal conflict – be helpful or be true to your own likes.

Or Person one is thirsty, too, but still decides to help Person two. Then we question WHY – which leads the story on.

Just this – is not a story.

Hi Fran,

Believe me, I’m a huge believer in conflict in stories (I’ve written tons of posts on the topic–LOL!). But I wanted to explore alternatives for those who write low-conflict stories, as I’m certainly not the “final word” on a topic. 😉

You might find my latest post interesting, as I dug more into what “a different approach to conflict” could actually mean–and how we can use that understanding even in our conflict-filled stories to keep readers more engaged. Thanks for stopping by!

[…] our way to the end of a manuscript can be fraught. Jami Gold ponders: does every story need conflict?; Hank Phillippi Ryan says if you need a good idea, make a list; Laurence McNaughton shares the 3 […]

This time maybe I am late but have read almost all of your posts. And it is very helpful while writing my upcoming storybook. Thank you very much Jami Gold. You are real gold for me.

Very interesting article, thanks! I wonder if it’s simply a question of how we define conflict? Perhaps it doesn’t necessarily mean arch opposition, but could alternatively be understood as any kind of opportunity (which implies some kind of lack or potential, some circumstance to which someone can respond). In this way, the kishōtenketsu story does have a kind of ‘conflict’ in the guy who is sitting there with nothing to do, a bit sad, perhaps lonely, and the other responds by offering them a drink, completely changing their mood. This conflict-resolving gesture gives you an emotional jolt, and carries quite a lot of power. An alternative response to the conflict may be for the drink person to deliberately ignore the other one, out of apathy (low emotional impact) or aversion (higher emotional impact). Or a story without conflict altogether could be that the drink person didn’t even notice the other one, and the two never engage. That really is a no-conflict, no-story story.

Hi Clare,

Yes, well stated! I often think of conflict as “gaps” between what is and potential, so I definitely have a broader view than many. So I like the way you worded the variations possible. 🙂 Thanks for sharing!